- Home

- Jeremy Robinson

The Distance Page 6

The Distance Read online

Page 6

A loud squawk snaps my head up. I turn and look out of my open door. On the side of the road, a raven, its black feathers fluffed up, wrestles with a second, a single wrapped ice cream bar held in both beaks.

“There’s two,” I say, and then I realize what I’m seeing.

Life.

The birds survived.

Maybe other people did, too?

I close the door and start driving. Destination: home. There’s no real strategy to the location aside from comfort, but it’s a direction. Something to focus on. That and the birds. If there are birds, there could be other animals, and if that’s true, then there have to be people. I tell myself this, over and over, throughout the long drive through the desert, during which I don’t see another living thing.

9

POE

The big, neighbor dog peers at me sideways, front paws on a kitchen chair. He commits three more vigorous, slurping licks to the leftovers and then arcs joyfully down from his meal, to my side. He barks once, sits and wags his tail.

“I guess I didn’t shut the door very tight,” I say to him, and bend down, rubbing him behind his ears. I sigh and check his tags. Pulse returning to normal, I recognize how soothing this animal’s presence is to me.

“Luke, huh? As in Skywalker?” He barks and licks my face. Sylvia continues to bellow, ready to burst if she isn’t milked soon. I think I’ll put James in with her...after I collect some milk for myself. Luke and I can’t possibly drink as much milk as she produces.

All these animals, suddenly mine. I sigh again, more of a groan this time. My parents raised me with farm animals, and I understand them, but like many people’s childhood constants, they’re something I tolerated as normalcy, but didn’t choose for my own independent existence. Animals annoy me with their routine neediness. They keep you at home, and attached.

Luke and I head out to the barn, the familiar tang of hay, manure and warm mammal bodies so consoling I nearly lie down. Surprising, this sudden sense of home.

After cleaning a teat with an antimicrobial wipe, I sit on the milking stool and go to work on Sylvia, her udder tight and bloated. Luke keeps trying to stick his nose in the pail, and I shove him gently away with my bent leg. James, Sylvia’s calf, a fraction of her size with adorably large eyes, would probably like to have a go, too, but my parents keep them separate so she’ll produce milk. Continuing the practice seems like a good idea, given the circumstances. The chickens poke around, clucking, feminine. All these animals, so ridiculous.

All these animals. All alive and unharmed. Whatever happened to my parents and the neighbors didn’t affect the animals. They all seem fine, vigorous and healthy. How did they escape the same fate?

Finished, I give Sylvia and James a few pats, their furry coats soft due to my father’s frequent brushing and care. His hands were here, so many times. I need to watch the frequency of these thoughts. My eyes start to blur, teary. After pouring the steaming raw milk through a strainer, from one pail to another, I set it on the counter to chill and look around for a clean spot and sit down on the hay. Luke plops next to me, his head in my lap. Sylvia shuffles heavily, nudging my head with her snout and knocking my hood backward. James shoves his snout through the slats looking for more attention, or maybe just reminding me to put him in with his mother. All these creatures to care for. What the hell am I going to do?

I feel a slight whirl of nausea and realize that in my overwhelmed state of mind I have forgotten the most important creature of them all.

“Sorry, Squirt,” I whisper, my hands across my belly. I stand up and look at the dog. “Time to pull our shit together.” I move James in with his mother and he assaults her udder, nudging with his nose and then drinking. Steaming bucket of milk in hand, I walk back to the house, imagining what it will be like to do this thirty pounds heavier, most of it in the front.

Luke bounds through the snow beside me, eager for a drink, ignorant to the changes going on inside me. “Things are going to get harder,” I tell the dog. “But we can handle it.”

He continues vaulting about, burying his head in the cold snow. If only both of us could be so joyously oblivious.

“We can handle it.”

Before taking stock of the food stored in the house, I turn the television on, hoping there will be a live news reporter filling the screen, explaining the strange event that took my parents and neighbors. The first station is static. I switch to a second and flinch away from the screen. Big Bird and Cookie Monster are singing. I pause on the channel for a moment, feeling hope. I know the episode was recorded thirty something years ago. I recognize the song. But the voices and animated movements feel like life. Human life. Maybe it’s simply that something—anything—is still on TV, but it gives me hope.

The third channel confuses me. The camera angle is slightly askew, but I can make out something long and wooden, finished, like a piece of furniture. It’s a news desk. Empty. Devoid of anchors, and apparently, camera operators. I switch to another station, and this time, a clearer and closer shot appears. A news desk sits solitary in front of what should be a busy news room, but is just empty space and glowing computer screens. I check the station logo in bottom right. CNN. National news out of New York. Five hours away by car. The news ticker at the bottom shows snippets of news, now a day old:

President signs immigration bill into law despite vocal opposition...

Hochman’s patients have gone missing in Memphis, Chicago and Boston...

Severe Winter Storm Warning for Northeast Coast. Power outages expected. Whiteout conditions...

“No kidding,” I say and glance away from the text. That’s when I see them.

Two people.

What’s left of them, anyway.

Two small piles of white powder sit atop the news desk. One is mixed with a necklace and framed by earrings. The other mingles with an ear bud. I can picture the two news anchors, discussing who knows what, sitting in their chairs, elbows on the desk, maybe joking, maybe reporting on the storm, or the Hochman’s outbreak, and then...what? Did they react on camera? Did viewers see them disintegrate? Or did no one see the spectacle because they were too busy dying?

I sit down hard on the braided rug and scoot back toward the couch, clutching my knees to my chest. I stare at the TV.

How many people?

Luke trundles in, belly full of leftovers, and schlumps down next to me, tail thumping. My mind is blank. I feel empty, eye of the storm calm. I reach behind me, tug the afghan down from the couch and pull it over my head, like I used to as a child—instant fort. Luke noses his way under, one eyebrow raised in curiosity. We sit there breathing, the three of us, for a long time, spots of light between the knitted knots. I pick up the remote and switch the channel back to Sesame Street, peering out through the holes in the blanket, my fingers clutching the spaces between. Bert is doing the pigeon dance.

An hour later, I investigate my parents’ house. Stocked fridge, generator running, we’re good for at least one week, or several if I first eat what will expire soonest. Kitchen cabinets reveal a variety of canned goods, dry perishables like Honey Nut Cheerios and my favorite, cinnamon graham crackers, purchased by my parents specifically for my visits. So, we’re not going to go hungry any time soon.

There is also a freezer in the cellar, filled with my dad’s pies and frosty, slaughtered, vacuum-packed chickens. It’s a good thing I turned on the basement breaker, I realize. Along with the equipped freezer, home-canned soups, jams, spaghetti sauce and pickles line the shelves along two walls in the basement—mostly my mother’s work, her garden ever-generous. But if I can avoid going down there for a while, I will.

I wash all the dishes, the well-pump still functioning with the generator’s assistance. And then I sit at the table, my head in my hands.

My mother’s face, crumpling inward. The look on my dad’s face, his voice, ‘Poesy,’ his hand on my arm. With my fingertips I graze the spot on my arm where he last touched me, between m

y wrist and elbow. It’s a little tender still. He held on hard. My mom had patted my back, right here in the kitchen, her thin frame a tiny shift in the air. Her wispy self, right behind me, draped knit shawl. I can’t help it, I turn and look.

Hopelessness bends my body down until I am lying on the kitchen floor, my cheek against the frigid, old linoleum. I feel a little bit like I want to die, too, and maybe I will just welcome the darkness. I’ve faced depression before, but nothing like this. This is drowning. An inescapable depth. Sinking, rocks in my pockets.

Luke canters over and licks my face, tasting salty tears. He goes to the kitchen door and paws at it, whining. I’ve never owned a dog before. It’s an unceasing chore, but his constant needs are like a hand reached over a precipice, keeping me from falling.

“I’m coming,” I groan from the floor.

I sit up, hands on my bent knees. I feel dizzy with confusion and sadness. These creatures, dependent on me, Squirt, Luke, the cows, the chickens. They will propel me to move off the floor, even though I don’t want to. I want to just lie here, halfway under the table, and go to sleep.

I wobble to my feet, though, and let the dog out. It’s freezing outside, and I lean against the doorframe, allowing my body to experience the frigid air, letting my brain flip over and away from the murky pond it was in a minute ago, there on the floor.

Just because my parents, the neighbors and the newscasters on CNN are now dust, it doesn’t mean that I’m alone. There could be other survivors. Somewhere in the world. Maybe even here in town.

I have trouble believing that my small parents, with their strange ways, were the only ones who knew or prepared for what was coming. There was nothing extraordinary about them. Nothing that set them apart, at least not from other UFO-fascinated survivalists, of which there are many. What happened to me could have happened to others.

They’re out there, I decide. There have to be at least a few. I just need to find them.

A shiver rumbles through my body, involuntary and cold. “Luke!” The dog’s head lifts out of a snow drift he’s mistaken for a snack. “C’mere, boy!”

He springs to life and runs to the door, waiting until he’s inside to shake the snow balls from his fur. “Mom would have serious issues with you.”

His reply—laying down on the antique braided rug in the living room, soaking it with his thawing wetness—says he doesn’t care. I turn back to the open door and the coldness beyond. I feel beckoned. Called to find another survivor. My conscious mind says this is unwise. Outside is freezing. Maybe dangerous. My subconscious supplies the impetus to embrace bold action.

Prenatal vitamins.

My parents didn’t believe in vitamins, their feeling that humans receive everything they need from locally grown, nutritious food. I, however, am a bit less crunchy, and I will ingest things from bottles if I feel they’re necessary. Or fun. Or delicious. Squirt and I need more support than jarred produce can provide. If I had known I would be here longer than a single night, I would have brought my supplements. But who could have predicted this fate?

No one, I think, and then correct myself. My parents.

I decide to leave the generator on, to keep the fridge and freezer cold, and the heat running, and head out to the barn to locate the snowshoes. The grocery store is two miles away, an easy walk for me...when there isn’t three feet of snow. On the way back to the house from the barn, the arctic air shoots straight through me.

Back inside, I wrap in layers—my mother’s fleece balaclava, Gore-Tex gloves, long underwear taken from her upstairs bureau drawer and my dad’s red coat, which comforts me. Snowshoes clipped on, I look like some kind of weird refugee from the frozen badlands of a sci-fi movie. I head out into the gleaming white world, the snowshoes doing their job, dispersing my weight and allowing me to walk (mostly) on top of the snow. Luke follows me out, his paws sinking, each step a leap. “It’s a long walk, buddy. You sure?”

He watches me with eager eyes, tail never tiring.

“Suit yourself.”

I walk out past my buried car, snow drifts looming taller than me. I wouldn’t be able to drive five feet without getting stuck. I consider taking my parents’ truck, but my car is in front of it. I feel like I want the walk, anyhow. Something to do.

The long, tiring snowshoe walk down my parents’ road, where the snowplows hadn’t begun to clean, takes over an hour. After exiting the wooded street, we pass a car, off the road, still running. I peek inside, tiny butterfly of hope in my gut, and am greeted with several heaps of clothing, white powder swirling around the interior, slipping across the dashboard and the seats, propelled by the car’s heating vents. I decide not to open the door.

Twenty awkward, snowshoe steps ahead is a big, red, Chevy truck, its hood bisected by a pine tree, engine quiet. Again, inexplicably, the little flicker of hope. Maybe, this time, someone? And then a second thought, maybe someone who’s legitimately hurt, not powder, and in need of help after an accident?

As Luke and I approach, a hefty, black German Shepherd pops into view, just as Luke did earlier at the neighbor’s house, giving me a weird sense of déjà vu. He eyes us for a quiet moment, looking from me, and then to Luke. When he sees the dog, the shepherd becomes unhinged. It barks savagely at Luke and I think, for a moment, that this shepherd might just be afraid of other dogs, but then it turns toward me and intensifies. A strand of drool slaps against the glass. Sticks. Smears as the dog grinds its teeth, lips and snout against the window.

Startled, I tip over backward onto the partially snow-covered street. I’m still wearing the snowshoes, which I could have removed on this sort of cleared street, and I twist my ankle. The pain is sharp, but not in the grinding, broken bone way.

Luke is unsure what to do with this vicious creature and stands, head down, tail between his legs. He’s not a fighter, that’s for sure.

I remove the snowshoes and the boot on my right foot, then peel down my sock to inspect my hurt ankle. Throbbing, starting to swell. No, I think. No, not now, not here.

Snow soaks through my backside, freezing my legs and bottom. The dog keeps snarling at us, his scratching paws beating out a steady staccato beat on the glass, trying to break through the window.

“Asshole!” I yell at him and scrape up a mittenful of snow from the pavement, hurling it at the window.

I have now managed to enrage the dog more, and I watch his anger escalate, a weird, throaty, growling-wheezing combination. Intimidating as hell. But he’s got me pissed. At him. At everyone for dying. For leaving me alone. At whatever kind of God could allow something like this to happen. I stand to my feet, the pain fueling my anger. “Fuck you,” I tell the dog, the words flowing out low and sinister, but in a way a dog can’t understand. So I shout, barking the words, “Fuck! You!” And I punch the glass.

The dog flinches back, stumbling and falling into the door on the far side. But before I can feel good about establishing my dominance, he returns, unleashing his fury on the driver’s seat headrest, tearing it apart in seconds, and then striking the window so hard I hear a crack. Blood flows from the dog’s mouth, mixing with frothy saliva, as he continues his barrage on the glass.

I suddenly realize he might be able to break a window, and neither I, nor Luke, would be able to protect Squirt from that monster.

“I hope you rot,” I tell the dog, and I limp away, snowshoes tucked under my arm. I’m freezing, my butt is soaked and violent death is trapped in the car behind me, fighting to get out. That dog is just fighting to survive, I think and I look down at Luke by my side. Like us. But doomed.

10

POE

Crap, my ankle hurts.

As we walk, I examine my feelings. Limp, step, limp, step. Strange how the terror of that dog brought out my rage and steeled my fortitude a little. Fuck you, dog! Rot to death! I grin, just a small one. I can make choices. I am still in charge. I’ve got Luke and Squirt, and we’re walking to the store. The normalcy of it gives me peace.

I notice the trees, heavy with melting snow, bending down as though in reverence to my passing. A single branch vaults up as the snow slides away, snapping a salute. I give the maple a nod and carry on. Limp, step, limp, step.

I grow accustomed to the pain, and the reality of what I’ve just done floats to the surface. I just left a dog to die a slow and painful death. It will starve. No, it will die of dehydration before that happens. Both are horrible deaths. It feels...evil.

No, he would have killed Luke and bit your face off.

He was covered in powder.

Somehow, my brain short-circuited that part and saw only his black fur, but now, picturing it again, I realize he was covered in the white powder. Of course he was. But I still can’t let him out of the truck.

Maybe if I were alone. If Luke had stayed home and I’d never become pregnant and the world hadn’t ended so that the emergency room could sew my face back up. But here? Now? I can’t let that dog out, any more than I could put a gun to my head.

Sobered a bit by these thoughts, my heart softens for the animal the further I walk away from him. It strikes me, a punch in the gut, that there are probably many, many unattended pets and farm animals that will be in need of care. Parakeets in cages. Unmilked cows. Thousands of dogs, cats and guinea pigs, trapped in their homes, covering the interior spaces in poop and urine. Some escape and go feral; some just waste away. Sheep and goats, trapped in their foodless fencing. How many? Once again, I can’t fathom it. How many? Were other countries affected, too? I imagine wild creatures—lions and elephants—slowly taking over the savannahs once again. The reforesting of the temporal forests. Great apes. The flourishing of eco-systems. I push it further: tuna, whales, unfished oceans. The short run tragedy of humanity’s—and their pets—decimation are a long term win for the planet.

Alter

Alter From Above - A Novella

From Above - A Novella Flux

Flux Tether

Tether Exo-Hunter

Exo-Hunter Pulse

Pulse Cannibal

Cannibal Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller cta-5

Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller cta-5 Flood Rising (A Jenna Flood Thriller)

Flood Rising (A Jenna Flood Thriller) Viking Tomorrow

Viking Tomorrow Project Legion (Nemesis Saga Book 5)

Project Legion (Nemesis Saga Book 5) BENEATH - A Novel

BENEATH - A Novel Kronos

Kronos SecondWorld

SecondWorld XOM-B

XOM-B Forbidden Island

Forbidden Island Project Maigo

Project Maigo The Last Hunter - Descent (Book 1 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Descent (Book 1 of the Antarktos Saga) Jack Sigler Continuum 1: Guardian

Jack Sigler Continuum 1: Guardian Infinite

Infinite Project Hyperion

Project Hyperion The Distance

The Distance The Divide

The Divide The Last Hunter - Ascent (Book 3 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Ascent (Book 3 of the Antarktos Saga) The Last Hunter - Pursuit (Book 2 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Pursuit (Book 2 of the Antarktos Saga) Raising the Past

Raising the Past The Others

The Others The Last Hunter - Collected Edition

The Last Hunter - Collected Edition Threshold

Threshold Blackout ck-3

Blackout ck-3 Antarktos Rising

Antarktos Rising Viking Tomorrow (The Berserker Saga Book 1)

Viking Tomorrow (The Berserker Saga Book 1) The Didymus Contingency

The Didymus Contingency Savage (Jack Sigler / Chess Team)

Savage (Jack Sigler / Chess Team) Prime

Prime Insomnia and Seven More Short Stories

Insomnia and Seven More Short Stories Empire (A Jack Sigler Thriller Book 8)

Empire (A Jack Sigler Thriller Book 8) Unity

Unity Instinct

Instinct The Last Hunter - Lament (Book 4 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Lament (Book 4 of the Antarktos Saga) MirrorWorld

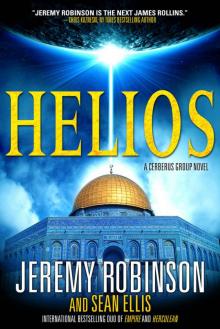

MirrorWorld Herculean (Cerberus Group Book 1)

Herculean (Cerberus Group Book 1) Island 731

Island 731 Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller

Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller Patriot (A Jack Sigler Continuum Novella)

Patriot (A Jack Sigler Continuum Novella) 5 Onslaught

5 Onslaught SNAFU: Survival of the Fittest

SNAFU: Survival of the Fittest Helios (Cerberus Group Book 2)

Helios (Cerberus Group Book 2)