- Home

- Jeremy Robinson

Cannibal

Cannibal Read online

CANNIBAL

A Jack Sigler Thriller

By Jeremy Robinson

with Sean Ellis

Description:

Still recovering from the tragic loss of a good friend, Jack Sigler, callsign: King, leads the Chess Team—a crew of former Delta operators—back into action. But what should be a routine snatch-and-grab to capture a drug cartel leader, escalates out of control, throwing the team into a challenge unlike anything they’ve ever faced. An enemy from their past, who is close to unmasking their identities, joins forces with the psychotic cartel kingpin, setting a trap that will shake the team to its foundations.

While the team battles enemies old and new, King’s fiancée, CDC disease detective, Sara Fogg, struggles to stop a strange outbreak that transforms the infected into ravenous, inhuman monsters. Once responsible for the disappearance of the Roanoke settlers, the disease now threatens to spread across the planet, ending human civilization in a bloodbath of violence.

Hunted by humans and monsters alike, King and the Chess Team face a desperate choice—sacrifice themselves or let the world bleed.

Jeremy Robinson and Sean Ellis, the international bestselling team behind Prime and Savage, return with a riveting and horrific tale reminiscent of Matthew Reilly’s and James Rollins’s best. Settle in for a long night as the Chess Team journeys around the world, through history and to your worst nightmares.

CANNIBAL

A Jack Sigler Thriller

By Jeremy Robinson

with Sean Ellis

Older E-reader device? Click here for e-book store.

Sean would like to dedicate this book to:

“Bonnie Osborne, the first person to believe I could do this.

Thank you, wherever you are.”

Special thanks also to Ian Kharitonov

for Russian language translation.

“And having well considered of this, we passed toward the place where they were left in sundry houses, but we found the houses taken down, and the place very strongly enclosed with a high pallisade of great trees...and one of the chief trees or posts at the right side of the entrance had the bark taken off, and five feet from the ground in fair capital letters was graven CROATOAN.”

—John White, Governor of the Roanoke Colony, August, 1590

“When a man is denied the right to live the life he believes in, he has no choice but to become an outlaw.”

—Nelson Mandela, 1995

And ye shall eat the flesh of your sons, and the flesh of your daughters shall ye eat.

—Leviticus 26:29

Prologue

Virginia Colony, 1588

“Run!”

The exhortation still rang in Eleanor Dare’s ears, but instead of offering the possibility of hope, it sent her reeling to the edge of the abyss.

Run? From that? Impossible.

Over the sound of her frantic breathing, the rustle of grass and the snap of twigs underfoot, the hungry snarls of her pursuers closed in.

So close.

A shriek erupted from the darkness somewhere off to her left, but it was almost immediately cut off, replaced by an unholy gurgling noise and the wet tearing of limbs being ripped apart.

She wondered who it had been, and she wanted to say a silent prayer for the soul of the fallen man. Instead, she found herself begging God that the man’s sacrifice might buy them just a few more seconds, and salvation for her, her husband Ananias and for little Virginia.

Ananias gripped her arm and dragged her forward faster than her legs could move, repeating that desperate word. “Run!”

She clutched her infant daughter closer to her bosom and focused on the bobbing flame of the torch. Eleanor knew little about the man holding it. John was the name he had given them, but whether it was his true name, who could say? He was an Englishman, a privateer, or so he claimed, who had washed up in their midst a few weeks earlier, warning them not to expect relief supplies anytime soon. England, he had said, was at war with Spain, and no ships would be spared. Ananias and several of the surviving elders had believed him, trusted him, so she had as well. It was he who had urged them to flee the trap that had been waiting for them at the Secotan village—though in truth, not much urging had been required. He had also advised against accepting the natives’ invitation in the first place. If only they had heeded his earlier admonition, there would have been no need for the latter.

He told us to go to Croatoan. We should have listened to him.

Virginia had been asleep just a few minutes ago when their flight began. Now she was wailing in protest at having been disturbed from her slumber, completely heedless of the horror that stalked them. Against all her motherly instincts to offer comfort, Eleanor ignored her daughter’s cries. The flame was the only thing that mattered.

The flame was life. Behind them, in the darkness, death waited.

“If you cannot silence the whelp,” James Hynde said, panting, from a few steps ahead, “I’ll dash its brains out and leave the both of you to them.”

John wheeled around, his blade glinting in the orange light and aimed at Hynde’s throat. The latter barely skidded to a stop before impaling himself on the point.

“No one will be left behind,” the privateer said, “except you, if you speak again.”

As soon as the threat was uttered, John turned back and resumed running. As Eleanor passed him, she saw Hynde swallow nervously, and then he, too, was running again.

Behind them, the crunching of bones diminished with the distance, then it fell silent altogether. Did the sudden quiet mean the brief reprieve was already at an end?

John stopped abruptly and began waving the torch over his head.

Hynde uttered a harsh blasphemy, while beside Eleanor, Ananias shouted, “Where are the boats?”

Eleanor realized that they had left the woods behind and were now standing upon the sandy shore, where they had made their arrival only a few short hours before. The Secotan village was here, on the mainland, but the fort, the home of Eleanor and the other members of the colony—those few who survived—lay on the eastward edge of the island the natives called Roanoke. Between the two lay a narrow marsh with a tangle of braided channels too shallow for a ship to pass through. The Secotan warriors had brought them to the village in their birch longboats, drawing the fragile looking craft up above the tide line when the journey was finished. Now, all that remained to mark the spot where they had landed were long grooves in the damp earth.

“They took the boats,” Hynde raged. “This was their plan from the beginning. Their bloody vengeance!”

Eleanor did not doubt that. It had been naïve to think that the natives would simply forget the violence that had been done to them. Yet, in her heart, she knew that was not the real reason for what had befallen them on this night.

God has cursed us for the evil that was done in our midst.

She hugged Virginia tighter, rocking her, murmuring soothing words that felt like a lie.

“Into the water,” John shouted.

Hynde and several others did not hesitate, but splashed out into the marshy shallows. Ananias however remained with Eleanor. “Not all of us can swim. And what of the child?”

A scowl crossed the privateer’s face. “Would you rather face—”

He broke off suddenly, dropping his torch and raising his musket. Eleanor gasped and turned involuntarily, following his gaze in the direction from which they had come. Her eyes could not penetrate the darkness, but her ears could. Something was crashing through the trees, something so large that she could feel the vibrations of its footsteps.

This cannot be, she thought. Unless…

The rest of the thought was too terrible to contemplate.

There was a faint huffing sound as the

privateer blew on the length of match cord attached to the gun, coaxing the ember to a cherry red. A click as he pulled the trigger brought it in contact with the powder charge in the firing pan. Even though she knew what was coming next, the report startled her. Through the sudden ringing in her ears, she could hear Virginia, no longer merely crying, but screaming as if scalded.

The privateer threw down the now useless musket and drew his sword. It seemed a paltry weapon against what pursued them, and Eleanor knew the man was almost certainly going to his death. He shouted something as he ran toward the shadows, perhaps urging them to keep going, or maybe it was just a battle cry. Ananias must have heard the former, for he scooped up the fallen torch, grabbed hold of his wife’s arm and dragged her into the shallows, following after the other colonists.

God save him, she prayed. If you will not save us, then at least spare him, for he is not a sharer in our sins.

The man did not seem the sort to simply throw his life away. Perhaps he was more skilled with a blade than she imagined, or maybe he had scored a hit with his ball, wounding or even killing one of their pursuers.

Even so, she did not think she would see him again.

Ananias drew her toward the water, but his steps were tentative and Eleanor knew why. Her husband, a London bricklayer who had never even crossed the Thames until the day he had boarded the ship her father had hired to carry them to the New World, did not know how to swim.

He would have to learn very quickly.

Something seized hold of her shoulder, and she cried out in alarm, trying in vain to pull away for a moment. Then, through ears that were still deafened from the noise of the musket, she heard a man’s voice.

John’s voice.

He was still alive, and shouting something into her face.

She gaped at him, wondering if he was…truly alive. That by itself was no source of comfort. He was barely recognizable. His clothes were torn and he was drenched in gore, but if any of the blood was his own, he was in the grip of some powerful demonic rage that made him immune to the pain.

Just like the others, Eleanor thought, frightened.

“Give me the child,” the man shouted again, and this time she heard. “I will carry her.”

Eleanor shied away, but even as she did, she realized that John posed no danger to her. If he had, he would have simply taken Virginia by force, probably from her dead arms. But to give him my daughter?

If I do not, I won’t be able to swim. I must trust this stranger. Mayhap God has sent him to deliver us from this curse.

She thrust the child into John’s hands, and she was surprised to see him cuddle the little girl close to his breast. It was an astonishing sight: her little child, not even a year old yet, being comforted by this tall, rough man who wore the blood of a vanquished foe like the war paint the savage natives sometimes used. Virginia was evidently not bothered by his appearance; her screams faded even as Eleanor’s hearing returned in full.

Ananias stared at him, incredulous, but he quickly overcame his disbelief and turned his eyes to the darkness behind them. “Are they—?”

“Dead. I killed two, but there might be more.” He plucked the torch from Ananias’s hand and somehow maintained his balance while holding the child in his left arm and keeping both the torch and his musket high and dry. Eleanor gathered her sodden skirts in one hand and continued forward, the water already waist-high.

After just a few steps, John shouted, “Here. Help me with this.”

Braving the uncertain marsh, Ananias plodded forward to join him, and a moment later, the two men managed to drag and push a fallen tree trunk out into the water. It sank with a splash, but then bobbed back up. It was tricky work with John’s arms full, but they succeeded.

John carefully laid his musket atop the floating log and proceeded to jam the end of his torch into the wood. The brand easily pierced the bark and went deep into the rotted wood. “It won’t bear our weight, but if you hold fast to it, you won’t drown.”

Working together, the three maneuvered the tree trunk out into the channel. As the water rose higher, almost to Eleanor’s throat, she threw an arm over the log and began to kick with her legs. She was not a strong swimmer and the treacherous conditions filled her with apprehension, but even death by drowning seemed a kinder fate than what would have happened if they had remained on the shore. Nevertheless, the wood was buoyant and although the water was cool, she found that the simple act of moving her legs, paddling like a dog, kept her mind off both the physical discomfort and the horror that they had just left behind.

Perhaps God has not entirely abandoned us after all.

It was easy enough for her to believe that he had. From the day they had set foot upon the shores of the New World, the colony had been plagued by one sort of misfortune or another. The worst irony was that they had never intended to establish the colony on Roanoke Island. It had been her father’s intention to settle further north, on Chesapeake Bay, stopping at Roanoke only long enough to take aboard the men of an earlier expedition who had garrisoned at a fort on the island. To their dismay, they found no one alive, but only a single unidentifiable skeleton. Yet, that had not been the worst of it.

The commander of their fleet, a Portuguese navigator named Fernandes, refused to allow them back aboard the ships, insisting that they establish their colony on Roanoke. Her father, John White, the colony governor, suspected that Fernandes secretly wanted a base from which to conduct privateering raids, but this was of little consolation to the one hundred and seventeen souls—including young Virginia, who had been born shortly after their arrival, the first child of English parents born in the New World—who were compelled to build a new life for themselves on the inhospitable outer bank island. It was already too late in the year to plant crops, and as the colonists soon learned, relations with nearby natives were badly strained. Their predecessors had massacred a native village after the alleged theft of a silver cup, and it could only be assumed that angry natives had wiped out the men of the garrison. The passage of time and an appeal to civility had not eased the tension, and soon thereafter one of the colonists had been murdered by the natives while gathering crabs on the north shore of the island.

Without enough supplies to last through the winter and with no reliable help from the native population, Eleanor’s father had made the difficult decision to leave friends and family behind, making the dangerous, late-season voyage back to England to gather relief supplies.

No one had been under any illusions about the tough days that laid ahead. Food stores had been rationed. The colonists had gathered what little they could and prepared for the coming of the snows.

Then the situation had truly become dire.

“Something is wrong.” John’s voice snapped Eleanor out of her musings. She looked up and realized that they were now within sight of the shore. The shadowy woods certainly looked ominous, but she did not immediately see the reason for John’s wariness. As soon as they reached the shallows and were able to stand, the privateer handed the now quiescent Virginia back to Eleanor, then quickly loaded and primed his musket.

“What do you see?” Ananias asked.

John shook his head as if to dismiss the question and raised a finger, warning them to silence, as he retrieved the nearly burned out stub of the torch.

The guttering brand held in John’s fist made Eleanor realize what was wrong about the situation—what the privateer had noticed right away. The fort was dark. There were no torches or lamps, no watch fires, not even the smell of wood smoke. Where were the forty souls who had remained? The able-bodied men who had been instructed to set watch fires to guide them home?

Figures began emerging from the shadows, drawn to the light of the torch, but these were the people that had escaped the village with them, those who had made the water crossing. Some of them, at least. Eleanor hoped the others had simply come ashore somewhere else.

John directed the men to gather behind him and the women be

hind them, then proceeded toward the gate, which stood open but unguarded. The privateer paused there, studying something on the ground, and then raised his musket as if sensing danger, before he proceeded inside. Eleanor reached the gates a moment later and saw what had arrested his attention. It was a basket, the kind used by the Secotan women for storing and transporting food. They had all eaten from similar containers back in the village, right before the nightmare had begun. This basket lay discarded near the gate, half its contents—pieces of cooked fish—spilled out upon the ground. Eleanor saw the wasted food and immediately felt a pang. Even now, on the cusp of summer, food remained scarce, too precious to be indifferently cast aside. But something about the basket frightened her, and a moment later, that clue also fell into place. The natives had brought food to the colonists who had stayed behind.

Eleanor’s heartbeat quickened as the full significance of this dawned, but it was already too late.

She heard one of the men gasp, and then John’s voice boomed, “Out. Everyone.”

Eleanor raised her eyes involuntarily. Oh, God. No.

The settlement had become a slaughterhouse. Everywhere she turned her gaze, she saw torn pieces of people she had once known, limbs, entrails and chunks of meat that were recognizable only because she knew they could be nothing else.

Ananias gripped her arm, dragged her back toward the gate. John’s musket thundered again, the sulfur smell of powder a sharp contrast to the foul stench of death that hung like a fog over the fortress. In the flash, she caught a glimpse of something moving, emerging from one of the houses. The shape was thrown back by the ball, but then just as quickly, it reappeared or was replaced by another.

Another shape moved in the shadows further down the square.

Alter

Alter From Above - A Novella

From Above - A Novella Flux

Flux Tether

Tether Exo-Hunter

Exo-Hunter Pulse

Pulse Cannibal

Cannibal Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller cta-5

Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller cta-5 Flood Rising (A Jenna Flood Thriller)

Flood Rising (A Jenna Flood Thriller) Viking Tomorrow

Viking Tomorrow Project Legion (Nemesis Saga Book 5)

Project Legion (Nemesis Saga Book 5) BENEATH - A Novel

BENEATH - A Novel Kronos

Kronos SecondWorld

SecondWorld XOM-B

XOM-B Forbidden Island

Forbidden Island Project Maigo

Project Maigo The Last Hunter - Descent (Book 1 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Descent (Book 1 of the Antarktos Saga) Jack Sigler Continuum 1: Guardian

Jack Sigler Continuum 1: Guardian Infinite

Infinite Project Hyperion

Project Hyperion The Distance

The Distance The Divide

The Divide The Last Hunter - Ascent (Book 3 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Ascent (Book 3 of the Antarktos Saga) The Last Hunter - Pursuit (Book 2 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Pursuit (Book 2 of the Antarktos Saga) Raising the Past

Raising the Past The Others

The Others The Last Hunter - Collected Edition

The Last Hunter - Collected Edition Threshold

Threshold Blackout ck-3

Blackout ck-3 Antarktos Rising

Antarktos Rising Viking Tomorrow (The Berserker Saga Book 1)

Viking Tomorrow (The Berserker Saga Book 1) The Didymus Contingency

The Didymus Contingency Savage (Jack Sigler / Chess Team)

Savage (Jack Sigler / Chess Team) Prime

Prime Insomnia and Seven More Short Stories

Insomnia and Seven More Short Stories Empire (A Jack Sigler Thriller Book 8)

Empire (A Jack Sigler Thriller Book 8) Unity

Unity Instinct

Instinct The Last Hunter - Lament (Book 4 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Lament (Book 4 of the Antarktos Saga) MirrorWorld

MirrorWorld Herculean (Cerberus Group Book 1)

Herculean (Cerberus Group Book 1) Island 731

Island 731 Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller

Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller Patriot (A Jack Sigler Continuum Novella)

Patriot (A Jack Sigler Continuum Novella) 5 Onslaught

5 Onslaught SNAFU: Survival of the Fittest

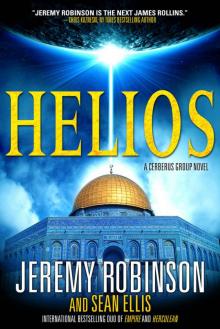

SNAFU: Survival of the Fittest Helios (Cerberus Group Book 2)

Helios (Cerberus Group Book 2)