- Home

- Jeremy Robinson

The Divide Page 5

The Divide Read online

Page 5

“Quiet,” he whispers, but it’s not possible. The water rushing around us is making enough noise to attract the attention of anyone on shore.

When I nod, he removes his hand and points to the riverbank behind us. I turn slowly and spot five men, a hundred feet back. They’re moving slowly, searching the water’s edge. They will find the cable, and if we’re still here, us along with it.

“My pack is too heavy,” I tell him. “See the machete?”

He looks back and nods.

“Can you take it?”

He draws the blade and sheath from the backpack and then I slip out of it. The pack, its contents, and the bedroll are luxuries I can do without. Food is everywhere, if you know where to look. The summer air provides all the warmth I need, and I’ve slept in far worse places than a tree without a bedroll. Only my father’s machete, and the knife on my hip are irreplaceable.

I hold the backpack under the water, drowning it and the gifts it contains from my father. When bubbles stop roiling to the surface, I release it. The pack is swept away into the dark depths. While my heart is heavy at its loss, my body feels half the weight.

Shua hands me the sheathed machete and I slip it into my belt. Then, without a word, we set out along the taut cable. Hand over hand, our progress is slow and waterlogged. Each pull forward into deeper waters increases the pressure against my body. My arms ache as I resist a river said to be powerful and deep enough to wipe away the Golyat.

Deeper waters bring colder temperatures, and my muscles begin to shiver from cold and exertion. Despite being twice my size, Shua is faring no better. He pauses to look at me and glances back at shore. His determination falters, and when I look back, I see why.

My body says I’ve scaled a mountain, but we’re only two hundred feet from shore, with many thousands left to go. Even worse, Micha’s men have nearly reached the cable. When they find it, they’ll follow its course out into the water and see our two chattering faces staring back.

Maybe this isn’t how the Modernists crossed? I have trouble believing someone could resist the river’s current all the way across, not to mention forty people.

I look at the cable, following it into the depths. It doesn’t cut straight across the river. It’s at an angle.

“We need to stop fighting it,” I say, and when he shows no sign of understanding, I add, “We need to let go.”

A little more of his face is revealed as the saturated wraps concealing him are tugged down. Something about him is familiar, but as an elder’s son, that’s not really surprising. I know what Plistim looks like, and Shua most likely resembles his father. What the lowered mask truly shows is his indignation. His words back up his expression. “That’s insane.”

“You’re good at Jutsu,” I say. “I’m good at insane. And not dying.”

His eyes go wide with fright. A moment ago, I wouldn’t have thought the man capable of fear, but the look in his eyes is unmistakable, and has nothing to do with my idea.

“What is it?”

“Something bumped me,” he says.

“I bumped you,” I say, as the river continues to thrash our bodies together.

“My feet,” he says. “Hard.”

His feet are a good eighteen inches beyond mine.

That’s when I see it, cutting through the water.

A fin.

I point it out. “There.”

The foot-tall fin hints at the shark’s size. I can’t identify the species based on a fin, but its size suggests a man-eater. The ocean and I aren’t fast friends. I spend most of my time in the forest, and have never faced a shark. But I have seen the remains of unlucky fishermen, and I know a single shark can inflict far more damage in a single bite than a dozen mountain lions.

A vibration runs through the cable, tickling my fingers. Shua has let go, and as I’d hoped, the current has launched him away at an angle. I take one last look back at shore—the men are closing in—and I look at the shark, making a wide circle. Then I let go.

Water rushes over me for a moment, and then the carabiner slips over metal and I’m carried downstream and across the river at the water’s full speed.

Which I now know is about half the speed the shark can manage when swimming with the current.

8

Shouts cascade from the shore. Short excited barks. Wild dogs with a fresh kill. Micha’s men have found the cable. When the voices turn angry, I know Shua and I have been spotted. When anger turns to laughter, I know they’ve seen the shark, closing in.

I’m far enough from shore to not be recognized, so the men probably think we’re with the Modernists, lookouts perhaps, going to warn the others. If we can survive the river.

“How do I stop it?” I shout, as the river whisks us further away from shore and downstream.

“I’ve only been to the ocean twice.”

His words enrage me. How can a man who spent his life training to fight not learn how to fight against the things in this world that most frequently harm people? Murder is uncommon. War is unheard of. We live on the fringe, and aside from the Modernists and the occasional legal combat, humanity is united.

While the current hurtles me along, I focus on the fin and try to keep my head above water. I draw the machete and hold it out in front of me the same way I would while facing a lion or bear. Predators are fierce killers, but like most living things, they’re not fond of pain. Unless they’re defending their young—or starving—a sharp poke is sometimes enough to make them think twice.

But this is a shark.

Are sharks even smart? I’ve always pictured them as mindless eating machines, or violent bullies. While some fishermen have been consumed, many more have been bitten and released. Some have lost limbs. I’ve never been able to think of a good reason for this behavior beyond, sharks are assholes.

I cough and sputter as churning water rolls over my head and down my throat. When I recover, the fin is gone.

The frothing dark water is impossible to see through, despite the late-morning sun blazing down upon it. I can see the blue sky reflected on its surface more than I can beneath it.

Machete still outstretched, I slip beneath the water, holding my breath. It’s quieter beneath the surface. Almost peaceful. Beams of yellow light shimmer down from above, reminding me of the green aurora that sometimes decorates the sky. The moment’s beauty is cut short when a long, sleek body slips through the beams of light, partially lit like an apparition. It maintains a steady speed with little effort, its course unwavering and unquestionably toward me.

Though I can now see my adversary, there’s not much more I can do than hold the blade out and wait. The shark twitches and somehow cuts the distance between us in half. Its black eyes glare. Its body goes rigid. And then with another burst of speed, it comes.

Just as quickly as the creature attacked, it turns away, just a foot from the blade’s tip. It couldn’t have seen the blade, I think, the eyes had closed and gone white as it rushed in. But it seemed to sense the weapon and understand its purpose.

Out of air, I surface and take a deep breath.

We’re nearly halfway across the river now. Micha’s men, small dots on the shore, which might include Micha himself, rush toward the line’s end.

How long will it be before they follow? Minutes, I decide.

Will the shark sighting deter them? Unlikely.

If Shua and I reach the far side with our limbs and lives intact, we’ll need to keep moving. While I have a low opinion of Micha, he’s smart enough to figure out how to use the cable, especially after his men watched us being whisked away by the water.

“Where is it?” Shua shouts. He’s five feet ahead of me, face still covered, but the brave man who came to my rescue is now lost in a torrent of water and fear.

“Take out your weapon, and come under!” It’s more of a command than a suggestion, and I don’t wait to see if he obeys. With a gulp of air, I slip beneath the surface once more, ready to face our attacker

and maybe a gruesome, thrashing death.

The shark is there, and easy to find, cutting an agitated circle around us, looking for the best angle of attack, which is going to be Shua, if he doesn’t get his head underwater. My frightened partner announces his arrival with a bubbly shout. Despite the loud declaration of his fear, his hands work fast, freeing the various parts of his spear from his hips and assembling them. When he’s done, the long spear will provide him far more protection from the shark than my machete, which is probably why the shark snaps its tail and returns to stare at me.

The predator moves back and forth, biding its time, perhaps waiting for me to surface again, which I’ll have to do in a few seconds. Just as my chest begins to tighten, the shark swims deep, beyond the sun’s reach.

Where are you?

My lungs burn.

Pressure builds in my head.

I have to fight to keep my mouth closed. If I open it, instinct will force me to breathe in.

I need to surface, but if I do—

The shark slips back into the light, its tail a flurry of motion, its body rocketing up toward me, triangle teeth bared, white throat gaping. I try to angle myself downward, but the carabiner and the swift river conspire against me. The best I can do is pull my legs up and hold the machete down.

When the shark is ten feet below me, a fraction of a second from striking, my body overrides my mind. Lips part. Water rushes in. My head breaks the surface, coughing and then gasping. Somewhere in the back of my mind, I register a swirl of water opposing the river’s flow for just a moment, and then I gasp again.

Did the shark turn back? Was my leg’s dismemberment so fast and precise that I have yet to feel it?

Though I have two deep breaths in me, my lungs are far from satiated. Despite this, I clamp my mouth shut and plunge beneath the surface again.

When the bubbles clear, Shua is revealed, still under, still clutching his spear, but struggling to hold on. The shark is impaled on the tip, wriggling back and forth. With a cloud of red, the shark yanks free and disappears into the dark with a burst of speed.

I don’t think it will return, but with blood in the water, its brethren might come looking.

Shua and I rise together, both coughing, desperate for air, and dry land. Despite having saved my life again, there’s nothing noble or brave left in the man. The part of me that was humiliated to need saving is glad to see this side of him. The rest of me wishes his brave countenance would return. There was comfort to be found in it.

Our rapid course across the river slows, taking my attention away from Shua. The water here is divided into strange, flat sheets that appear to defy the river’s flow. And then, we’re motionless, captured in one of the placid sheets. It takes me a moment to realize what’s happening. I’ve seen it before, but only from a distance. “The river’s current is fighting the incoming tide.” I point to the river’s far side. “Look, the current.”

Despite the river’s continuous flow, it’s currently battling the ocean’s mighty tide. The result is a seaward current behind us, and an inland current ahead. We’re caught in the space between.

“Pull yourself forward,” I shout.

Shua follows the command, but is slowed by the spear in his hand. While I quickly slip the machete into my belt, he’d have to waste time dismantling the spear. With sharks and blood in the water, I doubt he’d want to relinquish the spear anyway. So he pulls with one arm. At first, I think he’s moving slowly, but then I realize he’s matching my two-armed pace.

After a few hard pulls we reach the cable’s end, where it is attached to a large stone rising nearly to the river’s surface. Beside it is a second mounted cable, stretched tight across the river, following an upriver course. The design confuses me until I remember the incoming tide. The outflowing river and incoming tide have created a vortex, and we’re in the middle of it. Had the tide been flowing out, we would have been stuck here until the waters reversed.

“We need to switch between the cables.” I point to the second cable, just under the waterline. Shua grips my arm when I detach the carabiner and nearly slip away. A moment later, I’m attached to the second line. Shua repeats my actions with more grace, and we slip into deep water once more. The inland ocean current tugs us along, speeding us toward shore, completing a massive V through the river.

We remain vigilant throughout the remainder of our water journey, but the shark does not return, and if others have been drawn by the blood, they don’t find us. If we’re lucky, they’ll head for the far shore, now out of sight, where Micha and his men have no doubt started crossing the river.

I shout in surprise when my feet strike something solid. Then I realize it’s the rocky riverbed. A moment later, we’re in waist deep water, fighting the rushing tide as we unclip the carabiners and scramble toward shore. Chilled through and exhausted, my walk becomes a crawl as I move onto dry land. Shua isn’t faring much better, his strong body brought low by the journey.

Despite our condition, I can’t help but smile. Part of me is thrilled to set foot on Suffolk’s forbidden land. I glance up at the trees, a mostly leafy green with the occasional pine, identical to the land we left behind. Even smells the same. Of flowers. Of warm, damp rot. Of the ocean, and the river. This land is alive. And as far as I can tell, free of the Golyat’s corruption.

“We should keep moving,” I say, pushing myself up onto shaky legs. Each step is a challenge, and will continue to be until we rest. My preference would be to rest here, but it won’t be long before Micha and his men arrive. They’ll need to rest, too, but I doubt they’ll want to share the beach.

Shua pushes himself up and stands a bit easier with the help of his spear.

I take the machete to a nearby tree, severing a fairly straight branch and then shaving it clean of twigs and leaves. With my weight supported by the staff, I step into the dense woods that, until the Modernists’ arrival, had not been touched by mankind for five hundred years, and yet, will soon be covered in its blood.

9

With a half hour of hiking between us and the river, we come across a large flat stone at the center of a clearing and decide to stop for a rest, and a chance to dry out in the hot sun. Without a word, both Shua and I begin to shed our clothing, hanging them on branches to dry. Wet clothes are not only uncomfortable and cause chafing, but they restrict movement.

Shua’s lack of shame matches my own, and we’re soon both naked. His body, like mine, is fit, his lean muscles punctuated by scars. The difference between our scars is that mine are mostly jagged, from teeth, claws, branches, and stone, while his are almost all clean, straight lines—the kinds of wounds only a sharp blade can deliver.

While his scars tell the story of a man who has been trained in combat, and seen his fair share, his face remains a mystery, wrapped in a brown shroud. “I bare myself to you and you’re not courteous enough to show me your face?”

He laughs at the joke, giving me a once over. “Nothing I haven’t seen before.”

While he finishes draping his loose clothing, which has absorbed significantly more water than my tight garb, I inspect the strange stone. Aside from a few damaged areas, its height is even. There are a few cracks where vegetation has sprouted, and a large hole from which a tree has grown. The surface and sides are pocked from weathering, but it’s really just a big slab of porous stone. “I’ve never seen anything like this.”

“They were destroyed in New Inglan hundreds of years ago,” Shua explains. “Along with most other creations of the Time Before.”

“This isn’t natural?”

“Have you ever seen a perfectly flat and square stone before?”

Now that he’s pointed it out, I feel foolish for asking. So I propel the conversation onward. “What is it?”

“A building foundation.”

“People built huts on flat stones?”

“It’s not really a stone,” he explains. “It was something like a liquid, poured into a frame and

allowed to harden. It formed a very strong base upon which tall structures could be built.”

“Like in Boston.”

He nods, and sounds a bit wistful when he says, “Buildings far larger than the Golyat.”

He knows a lot about the Old World, which isn’t surprising given his father’s identity. While my father rambled about his knowledge to a daughter he didn’t quite realize was paying attention, Plistim is known for telling the elder’s sacred knowledge to anyone willing to listen.

Shua motions to my thigh, where the stitches Grace gave me are holding up. “Something bit you?”

“Mountain lion.”

“You killed it?” There’s a trace of dubious machismo in his voice.

“And ate its heart, before killing its mate.”

He pales a little bit at that, but I don’t think it’s because I killed two lions. “It’s true, isn’t it?”

He looks away from the wounds. “What?”

“About Aroostook. You don’t eat raw meat.”

He turns. “Haven’t for more than a hundred years.”

“What?” I’m staggered. It’s a gross violation of the Prime Law and puts Shua and all of Aroostook dangerously close to being Modernists. What would happen if an entire county was declared an enemy of the Prime Law? War? Mass murder?

He’s still smiling under those wrappings. “Piscataquis, Penobscot, and Washington, too. And all of the wildlands and Brunswick, of course.”

I’m beyond words, managing only a few strained grunts.

“All of the elders know,” he says. “We are distant enough from the Divide and have been cooking food for a century without incident. It’s safe.”

“It’s—”

“Against the Prime Law,” he says with a nod. “The Prime Law was amended a hundred years ago, leaving several former laws to the discretion of each elder. While most counties’ elders opted to maintain the old laws, those furthest from the Divide loosened them.”

“That’s moronic.”

Alter

Alter From Above - A Novella

From Above - A Novella Flux

Flux Tether

Tether Exo-Hunter

Exo-Hunter Pulse

Pulse Cannibal

Cannibal Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller cta-5

Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller cta-5 Flood Rising (A Jenna Flood Thriller)

Flood Rising (A Jenna Flood Thriller) Viking Tomorrow

Viking Tomorrow Project Legion (Nemesis Saga Book 5)

Project Legion (Nemesis Saga Book 5) BENEATH - A Novel

BENEATH - A Novel Kronos

Kronos SecondWorld

SecondWorld XOM-B

XOM-B Forbidden Island

Forbidden Island Project Maigo

Project Maigo The Last Hunter - Descent (Book 1 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Descent (Book 1 of the Antarktos Saga) Jack Sigler Continuum 1: Guardian

Jack Sigler Continuum 1: Guardian Infinite

Infinite Project Hyperion

Project Hyperion The Distance

The Distance The Divide

The Divide The Last Hunter - Ascent (Book 3 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Ascent (Book 3 of the Antarktos Saga) The Last Hunter - Pursuit (Book 2 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Pursuit (Book 2 of the Antarktos Saga) Raising the Past

Raising the Past The Others

The Others The Last Hunter - Collected Edition

The Last Hunter - Collected Edition Threshold

Threshold Blackout ck-3

Blackout ck-3 Antarktos Rising

Antarktos Rising Viking Tomorrow (The Berserker Saga Book 1)

Viking Tomorrow (The Berserker Saga Book 1) The Didymus Contingency

The Didymus Contingency Savage (Jack Sigler / Chess Team)

Savage (Jack Sigler / Chess Team) Prime

Prime Insomnia and Seven More Short Stories

Insomnia and Seven More Short Stories Empire (A Jack Sigler Thriller Book 8)

Empire (A Jack Sigler Thriller Book 8) Unity

Unity Instinct

Instinct The Last Hunter - Lament (Book 4 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Lament (Book 4 of the Antarktos Saga) MirrorWorld

MirrorWorld Herculean (Cerberus Group Book 1)

Herculean (Cerberus Group Book 1) Island 731

Island 731 Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller

Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller Patriot (A Jack Sigler Continuum Novella)

Patriot (A Jack Sigler Continuum Novella) 5 Onslaught

5 Onslaught SNAFU: Survival of the Fittest

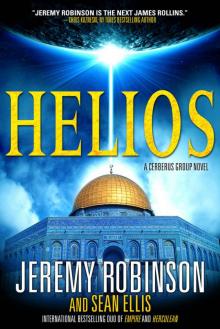

SNAFU: Survival of the Fittest Helios (Cerberus Group Book 2)

Helios (Cerberus Group Book 2)