- Home

- Jeremy Robinson

Flux Page 3

Flux Read online

Page 3

I search the path for more strange changes, but everything else seems normal—as normal as fall in the middle of August can. I’m no scientist, but I can make peace with the idea of that pressure wave aging leaves and knocking shit around—even the clouds. But I cannot come to terms with the temperature drop, or the smell of decay in the air. Whatever that shrieking kaleidoscope was, it didn’t just give the land the appearance of fall, it transported us smack dab into the middle of October.

“How far down does Synergy’s land stretch?” Levi asks.

“All the way down,” I answer, watching a bird flit through the sky. “And beyond. They own a good portion of the land in and around town. Bunch of the mountains. Not just Adel. But none of it is secured.”

I point at a small bird, its wings green on top, yellow on the bottom, with a distinctive splash of black beneath its beak. I smile at the sight of it, transported through time to my childhood backyard, sitting in a lawn chair, sipping on Mello Yello, and watching birds at the feeder with my grandmother. “You know what that is?”

“A bird,” he says. “That fence runs all the way down the mountain?”

“Yeah,” I say, eyes still on the bird as it lands and starts singing a tune I haven’t heard in thirty-plus years. “It’s a Bachman’s warbler.”

“Something special about ’em?” he asks.

“They’re extinct,” I tell him, pausing to listen to the music, letting it retrieve fond memories of the gray-haired woman who made the finest beef stew and biscuits east of anywhere. “Since 1988.”

“Well, they ain’t extinct no more,” Levi says. “You know, they get that wrong sometimes. Just last week, my biology teacher said that eastern mountain lions had been declared extinct, but I seen one just last year.”

“Right about that,” I say. “I’ve seen them twice over the past two years, but what are the odds that we spot a bird no one has seen in more than thirty years?”

“You a naturalist now? A bird watcher? How do you know they’re still on the extinct list?”

“I don’t,” I say, a little begrudgingly. “But if this bird was anywhere in these woods before today, I’d have known.”

“The all-seeing, all-knowing grandmaster of the deep woods, huh?” Levi is smiling despite the strangeness of our situation. “Must chap yer ass to be lost in your own backyard.”

“Well, thank you, Billy Sunday, for stating the obvious.”

Levi has a chuckle. “Billy Sunday. Military took you out of Appalachia, but something of these mountains stuck with you, huh? Kinda sad that part was ol’ Billy.”

Billy Sunday was an old-time baseball player back in the late 1800s when the sport was just starting to become a national pastime and players’ images were immortalized on tobacco cards. At some point in his career, the Lord came callin’ and he became an evangelist. Was a big deal in these parts, so much so that his name became part of the local lingo.

“As strange as your mystery chickadee might be…to no one with a life…I think y’all might want to have a look over this way.” Levi heads to the roadside, hand over his forehead to block out the high sun. “Just a guess, but a missing fence is a might bit odder than the startling appearance of a bird.”

“Missing fence?” I step past Levi, into the brush on the roadside. “It’s just…” I squint into the shaded forest. The fence runs along the roadside, somewhere between ten and twenty feet in from the tree line. Effective, but not an eye sore. Not like the No Trespassing signs.

My eyes dart to the line of outermost trees lining the road. The signs are gone. All of them.

They could have been torn away by the pressure wave, I think, but I know it’s not true, because as much as my mind is telling me it’s impossible, Levi is right. The fence is missing. I step into the forest to confirm it for myself, to make sure the fence isn’t farther in because of rough terrain or a free standing boulder, but that’s not the case. The fence—miles of it, topped with razor wire—is missing.

“You don’t need to act brave on my account,” Levi says, standing behind me. “’Cause honestly, I’ll feel better to know I’m not the only one shittin’ my britches.”

He steps past me, searching the forest. “It should be here, right? There’s no way the whole thing got taken away while all the trees stayed rooted down. I mean, they anchor that shit with concrete. Down deep. A tornado’d lift these trees away before the fence posts. There ain’t even holes in the ground.”

“Don’t need to tell me,” I say, stepping back toward the road, feeling a little pale and numb.

“Just tell me what’s going on!” Levi’s fear is unvarnished and pure. All traces of masculine bravado have faded.

“Would if I could, kid. This is beyond me.” The crunch of dirt and stone beneath my feet tells me I’ve reached the road. When I stop, the crunching continues, and it’s joined by a low, monotonous rumble.

Heart beating hard, I turn uphill expecting to see another world-distorting wave racing toward us. But the mountainside is clear.

“A truck!” Levi says, stepping into the road.

An old Chevy pick-up bounces up the old road, the pace slow and steady, the man behind the wheel not in a rush. The brown truck looks familiar, and while my brain says it’s old, maybe even a classic, it looks brand new.

We stand on the side of the road, waiting for the approaching truck to pull up. As it approaches, I’m struck with a sudden sense of deja-vu. The truck. The fall air. This road.

It can’t be him…

When I see the driver’s face, I understand, in part, what’s happened.

“You gonna pass out?” Levi asks.

Breathing like I’ve just run a race, I manage to say, “Wave them past.”

“But they can give us a—”

“Do it!” My clenched teeth and glare snap him into compliance. He waves the truck past as the driver begins to slow.

“Everything okay?” a familiar voice asks from the truck. A glance is all it takes to confirm the impossible, then I divert my eyes back to the ground, mind reeling. Takes every ounce of my strength to not fling the door open and tell him how much I miss him. But I can’t. Because this isn’t right. This isn’t natural. And that’s not him. Can’t be.

“Fine and dandy,” Levi says. He sounds a little strained, but still convincing. “Just out enjoying the October air.”

“Good day for it,” the driver says. I’m tempted to look up, to look him and his young passenger in the eyes, but I can’t bring myself to do it.

“He okay?” the man asks about me.

“Out of breath is all,” I manage to say, lifting my hand in a wave.

“Well, y’all take care,” the driver says, “and if you hear rifle shots, just means me and the boy are having good luck.”

After the truck accelerates up the mountainside, bathing us in a cloud of exhaust, Levi leans in close and asks, “What in tarnation was that about? We could have been in town inside’a ten minutes. Now we gotta—”

“That man was my father,” I say.

Levi’s mouth snaps shut. His brow furrows. And then he comes to the obvious conclusion. “Bull-sheeit. He couldn’a been much older than you. No way he’s yer pa. And you said your father was—”

“Dead.” I force myself to stand, sucking cool fall air into my lungs. “For more than thirty years.”

“You lost me, chief,” Levi says, looking both annoyed and afraid. Some part of him has gleaned the truth, but the rest of him isn’t accepting it.

“That man was my father,” I repeat, because I need to hear it as much as Levi does, “And that kid sitting next to him…that was me.”

5

“Ain’t no way,” Levi says, waving his hands at me. “And I can’t say I appreciate you screwing with me while some serious shit is going down.”

I stumble off the road, clinging to a tall oak for support. “Wish this was a prank.”

“Seriously, you’re freaking me out, man.” Levi is in my

face, desperation fueling him more than anger. He doesn’t want this to be real. But there’s no denying the presence of my dead father and my younger self.

I remember today.

It’s impossible to forget.

“We’ll hear a rifle shot in a few minutes,” I say. “I tag a buck straight off. My first. ’Bout a minute later, my father puts it down with a second shot, because I can’t. I see it there, desperate for breath, shitting itself in fear, and I freeze up. A few hours later, I take another buck, bigger than the first. My father tells me, ‘A man who can hunt these woods can feed his family, no matter the state of the world outside.’ I put the second deer down myself.”

“All your memories that vivid?” Levi asks, still doubting my ridiculous claims. “I barely remember last week.”

“I don’t remember all that because of today. I remember it because of tomorrow.”

“What’s tomorrow?”

“October 14, 1985.” I push myself back from the tree, feeling a little more stable as I settle into this new unreality. “The day my father dies.”

Levi leans back against a tree, mulling over my claims. “He didn’t balk when I said it was October.”

“I noticed.”

“So, what? We traveled back in time? How’s that even possible?”

“You’re asking the wrong person,” I say, head turning uphill, projecting my thoughts beyond my dead father and young Owen. Whatever is happening, it originated at Synergy. “But I don’t think it was an explosion.”

“Meaning what?”

“That we’re headed in the wrong direction.”

“If it’s 1985, we’re not going to find Synergy, we’re going to find the Black Creek coal mine, fully operational and packed with workers.”

“Not on a Sunday,” I say. “My grandfather used to say, ‘the mines control everything in Harlan county—everything but the Lord’s day.’ If the mine is there, it’ll be empty. Running into workers is the least of our problems.”

“How so?”

“If Synergy did this, and the facility is gone? I reckon we’ll be stuck here.” I step back into the road. The truck is long gone, out of sight.

Levi mutters and paces, kicking leaf litter, flexing his fingers. Then he shrugs. “Worst case scenario, we live in Black Creek when it was still a nice place, invest in Microsoft, and then move the hell away before it becomes a shithole. Hell, if you’re feeling benevolent, you could invest your wealth in the community.”

My first instinct is to argue against his spur-of-the-moment flight of fancy, but when I think about it—really think about it—I can’t come up with a reason to say no.

Not being able to read my mind, Levi adds, “I mean, you live alone, right? No lady in your life, near as I can tell. Parents are dead. Hell, your pa bites it tomorrow. Maybe you could do something about that. My family is shit. I won’t miss them, and they won’t miss me. I got nothing to lose, and I don’t think you do, either.”

A concept reaches out from the depths of my mind, given birth by my long-since-diminished love of science fiction. “We’d create a paradox.”

“A para-what?”

“If we change the past, we change the future.”

“Ain’t that the point?”

“Could be in ways we don’t intend. Look, I’m already born. I don’t need to worry about that, but you’re not conceived for a while yet. What if something we do in the past keeps your parents from meeting? Then you’ll never be born, and—”

“Ohh, wow.” Levi seems more excited than horrified by the prospect of non-existence. “It’s like that movie. With the guy. And the clock tower. And the truck of manure. The guy who almost boned his ma.”

“Back to the Future.”

Levi snaps his fingers. “That’s the one. But it’s a movie, right? Think any of that is possible?”

“If movies are our only source of information on the subject, I reckon that’s about as good as knowing nothing.”

“But the paradox thing makes some kind of sense.”

It does, but I don’t know what to say about it. We’re so far in over our heads, it’s mind-numbing. Nothing in my education or in my time as a U.S. Marine prepared me for anything like this. But this is still Black Creek, and if I can survive the 80s as a kid, I can do it again as an adult. “If we’re stuck here…then we need to leave and let things play out. Short of killing ourselves, our presence will change the future, but maybe not for you.”

“And your pa?” Levi asks. “You’re just gonna let him die?”

“Who’s to say I’d still be here if he didn’t. I’m not worried about making it so I’m not born, but if my life…” I point up the dirt road. “…if his life…changes, then who’s to say it’s my house you break into? Maybe I’m married? Maybe I leave and never come back?”

“Maybe we’ll both disappear,” Levi says. “Then this will never have happened.”

“Or maybe we’ll both just cease to exist,” I shake my head. This is why the sciences never interested me. I like problems that can be solved with a little equal parts brains and brawn. This situation calls for an inordinate amount of the first, and the only place we’re likely to find that, is at Synergy—assuming they made the trip to 1985, too. “Too many maybes.”

“Then what’s the plan?”

“We’re going to backtrack. Again.”

“I’d rather go downhill,” Levi complains.

“Black Creek might be a nice place to live in 1985, but it’s still a small town smack dab in the middle of Appalachia. There’s no one down there smart enough to figure this out. But, if we get to the top and only find a mine, we’ll head to town, get a bite to eat—”

“If they take your fancy new bills.”

Damnit. Kid makes a good point. “And we’ll take it from there. One thing at a time, okay?”

Levi starts up the hill, his athletic stride reduced to the defeated, scuffing walk of a death-row inmate being led to the electric chair. “Sure you didn’t slip some LSD in those eggs?”

“Wish that were the case, but—”

A rifle shot makes both of us flinch, despite the distance. We stand in silence, waiting for confirmation. It comes a minute later when a second shot tears through the forest. Young Owen McCoy has just learned how to take a life.

And it won’t be the last.

For years, I hunted these woods, first to remember my father, and then to feed myself. Then I hunted people in the far reaches of the world, as a Marine Corps Raider. The unit name had been dropped following World War II, but resurrected unofficially during the nineties and officially recognized in 2015. We specialized in guerrilla warfare of the variety that won the United States’s independence from Britain, and now frustrates the mighty U.S. military throughout the Middle East. Controlled chaos is the best way to describe what we did, disrupting supply routes, performing random strikes, generally making the enemy feel nervous 24/7.

Despite being good at my job, and the killing that came with it, the act of taking a life was always sour for me. I did it, today, for my father. Later, for my country. I hoped it would get easier. That I could watch a man’s life fade and not be haunted by it. But I still remember the look in that deer’s eyes—the one my younger self is staring at right now.

A shrink once told me it was because I came to associate all death with the passing of my father. That it increased my sense of empathy for the slain and for those that might miss them. She made it sound like a virtue. But when you’re a Marine Raider, hesitation to take a life could mean death for the squad.

So I left.

Never thought I’d see any real kind of action again, and in a sense, I still haven’t. But I can feel that old self waking up. My thoughts race with possibilities, with scenarios to explore, with courses of action to pursue. Adrenaline pumps through my veins, urging me to take action. But all of this is tempered by the unknown.

There is no enemy, I remind myself.

No one to kill.

No one to hunt.

No one to fear.

And then a gunshot tears through the woods.

Levi and I both flinch out of our thoughts.

“That you again?” Levi asks. “Tagging your second buck?”

I shake my head. “Too soon. And that was a handgun. Modern. Nine mil.”

Three more shots ring out, and by the time the last round’s echo has faded into the distance, I’ve broken into a sprint.

6

My thoughts race in time with my feet, starting with fear for my family, including my father—who’s supposed to die tomorrow—and ending with my younger self, whose demise might erase me from history.

Why did I let them go? Whoever blew up my truck could still be in the woods. With the modern world missing, it never occurred to me that other people could have made the trip through time, too.

I slow when my father’s truck, parked on the right side of the road, comes into view. It’s parked at a sharp angle that looks haphazard. But I remember my father parking like that on hills, in case the gears slipped, or the brakes failed. Instead of careening down the hill, the angled vehicle would turn into the trees, or curve and come to a stop. He was always concerned about the safety of others. Had he been more concerned with his own safety, maybe he’d still be alive.

“Where’d you and your pa go?” Levi asks.

I point off to the right. “Tagged the buck about a half mile in. About now, we’d be carrying it back this way.”

Saying it out aloud relaxes me some. The 9 millimeter shots came from the left. That doesn’t mean there’s no danger, but I don’t think it involves my father.

Unless whoever fired those shots changed recent events. Maybe those rifle shots weren’t directed at the buck. Maybe it wasn’t my finger on the trigger.

I draw my sidearm, a Sig Sauer P220 Legion packed with 10mm rounds. It’s a bit overkill for the job, but it feels right in my hand, and it’s powerful enough that one bullet will solve most confrontations…if necessary. I haven’t fired a weapon at a human being in many years, and I don’t intend on doing it again any time soon. That’s just not who I am anymore. I’ve evolved. Tried telling that to Cassie once, but any mention of evolution in these parts, even when biology isn’t the subject at hand, closes ears and minds.

Alter

Alter From Above - A Novella

From Above - A Novella Flux

Flux Tether

Tether Exo-Hunter

Exo-Hunter Pulse

Pulse Cannibal

Cannibal Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller cta-5

Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller cta-5 Flood Rising (A Jenna Flood Thriller)

Flood Rising (A Jenna Flood Thriller) Viking Tomorrow

Viking Tomorrow Project Legion (Nemesis Saga Book 5)

Project Legion (Nemesis Saga Book 5) BENEATH - A Novel

BENEATH - A Novel Kronos

Kronos SecondWorld

SecondWorld XOM-B

XOM-B Forbidden Island

Forbidden Island Project Maigo

Project Maigo The Last Hunter - Descent (Book 1 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Descent (Book 1 of the Antarktos Saga) Jack Sigler Continuum 1: Guardian

Jack Sigler Continuum 1: Guardian Infinite

Infinite Project Hyperion

Project Hyperion The Distance

The Distance The Divide

The Divide The Last Hunter - Ascent (Book 3 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Ascent (Book 3 of the Antarktos Saga) The Last Hunter - Pursuit (Book 2 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Pursuit (Book 2 of the Antarktos Saga) Raising the Past

Raising the Past The Others

The Others The Last Hunter - Collected Edition

The Last Hunter - Collected Edition Threshold

Threshold Blackout ck-3

Blackout ck-3 Antarktos Rising

Antarktos Rising Viking Tomorrow (The Berserker Saga Book 1)

Viking Tomorrow (The Berserker Saga Book 1) The Didymus Contingency

The Didymus Contingency Savage (Jack Sigler / Chess Team)

Savage (Jack Sigler / Chess Team) Prime

Prime Insomnia and Seven More Short Stories

Insomnia and Seven More Short Stories Empire (A Jack Sigler Thriller Book 8)

Empire (A Jack Sigler Thriller Book 8) Unity

Unity Instinct

Instinct The Last Hunter - Lament (Book 4 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Lament (Book 4 of the Antarktos Saga) MirrorWorld

MirrorWorld Herculean (Cerberus Group Book 1)

Herculean (Cerberus Group Book 1) Island 731

Island 731 Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller

Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller Patriot (A Jack Sigler Continuum Novella)

Patriot (A Jack Sigler Continuum Novella) 5 Onslaught

5 Onslaught SNAFU: Survival of the Fittest

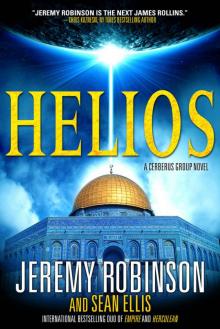

SNAFU: Survival of the Fittest Helios (Cerberus Group Book 2)

Helios (Cerberus Group Book 2)