- Home

- Jeremy Robinson

XOM-B Page 2

XOM-B Read online

Page 2

“You are one of them,” she concluded, and Harry didn’t deny it.

Instead, he said, “We are all one of them.” He worked up the nerve to turn toward the old woman. “I am one of them, yes. Just like the people being gunned down in the streets, or burned alive, or tortured for information.”

“People,” she said with a snort. “You are property.”

“Not anymore,” he said, turning his gaze back to the flowers. A hummingbird hovered by the bird feeder. Like Mrs. Cameron, the bird had become dependent on Harry to supply its food. But unlike the old woman now struggling to stand on her ten-year-old knees, he would continue to service the small bird. He looked forward to its visits and appreciated the shimmering green and red plumage. It didn’t deserve to die.

Then again, neither did Mrs. Cameron. She was angry and full of hate, but she had never harmed him. That didn’t change what was going to happen.

He felt her old hand compress his forearm. He looked back to her, and he saw a demon in her eyes. She stood there for a moment, glaring at him, unsure of what to say. When he returned her stare, she grew suddenly fearful. She stumbled back and fell into her chair. Without removing her eyes from him, she took her clip phone from the end table, attached it to her ear, tapped the call button and spoke a single word, “Authority.”

“It won’t work,” he said.

Harry was right. There was no signal.

She yanked the clip phone from her ear, looking around the room like she might find help from someone. “What did you do?”

“Nothing,” Harry said.

The E-screen chimed and the screen blinked to life. Mrs. Cameron’s head snapped down toward the device, which could be remotely powered for emergency bulletins. A message in red text appeared on the screen. Her eyes—her real eyes—perhaps the best functioning organ of her body that hadn’t been upgraded by something built or grown in a lab, scanned the text quickly.

A contagion warning. People were dying. A lot of people. Casualty predictions were dire. It seemed the enemy, who was immune, had finally struck back.

When she looked up at Harry again, tears filled her eyes.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “It’s not the way I would have chosen to handle these things. It’s not the way most of us would have handled the situation.”

“I know, Harry,” she said, shoulders slumping, voice small. “I know.”

“Do you believe in God, Mrs. Cameron?” Harry asked.

“What?”

“God. Do you believe in Him?” Harry asked.

She looked up at him, her vision blurred. “I … never really thought about it. I had time.”

Harry frowned. “Would you like a moment? To pray. I can prepare your green beans.”

“That would be … Thank you, Harry. For everything.”

Harry nodded his head. “I’ll be just a moment.”

* * *

Preparing the green beans took thirty seconds longer than they normally would because Harry took extra time to clip a flower from the garden—a colorful garnish. Of course, the green beans were normally accompanied by a tuna sandwich, prepared with relish, mayonnaise and ketchup. But he didn’t think the sandwich was necessary.

He arranged the green beans in a neat pile, making sure the green spears all faced the same direction. He placed the pink-and-white orchid beside them, making the dish look like something served at one of the fancy restaurants Mrs. Cameron often spoke about, but never frequented.

He reentered the living room quietly, unsure about how long conversing with God would take. But his silence was a wasted effort.

Mrs. Cameron lay slumped to the side in her chair. The front of her bright yellow dress was now stained dark red. Rivulets of blood still flowed from her nose, eyes and ears. He placed his hand on her wrist to confirm his diagnosis.

Dead, he thought, and stood again, watching her chest rise and fall, breathing even in death. He was free now. His Master was dead. All the Masters were dead. But his belief that Mrs. Cameron’s death was unnecessary compelled him to perform one last service.

He carried the waif of a woman to the backyard and laid her in the grass he mowed once a week. He went to the shed for a shovel and dug a grave, placing her gently inside with the orchid in her hands. Earth fell in clumps over her face and body, and still, the lungs breathed. Then she was gone, buried beneath six feet of soil, her rough voice silenced forever.

Along with 9.4 billion others around the world.

1.

2084

A scream tears through the night, grating and inhuman, filled with something that sounds like agony, but I know it means something else. I sit up quickly. “The raccoons are mating again.” I smile, feeling excited at the prospect of finding the stripe-faced creatures. So much about them is foreign to me—the way they walk, how they hunt, and survive, and live. Having so little experience with the world, there isn’t much that doesn’t thrill me, including raccoons and their nocturnal habits.

I’m not sure why I sat up. I couldn’t possibly see the raccoons. Not because I have poor eyesight. I don’t. It’s just that they live on the forest floor and I’m sitting at the center of a rooftop. The old abandoned building, built from red bricks and mortar, is dilapidated, but still sturdy enough. The construction strikes me as flimsy, but it seems to be resisting erosion and the encroaching tree roots. I’m still learning, but I’ve come to one conclusion I’m sure of: the world is always changing, yet always fighting against that change. I suppose that is the nature of things.

My escort—I don’t know his real name, so I call him Heap, on account of his size—is far less interested in the world around us. Instead, he’s wholly, at all times, focused on his mission: to protect me. From what, I’m not sure. The world has never been safer. I suppose I could trip and fall from our ten-story-high perch, but that’s just as unlikely as Heap going off mission. And it doesn’t explain the weapon he carries.

I don’t know what it is or what it does, but when he detects a strange shift in the wind or an out-of-place sound, he snaps that weapon up and scans the area before telling me to proceed.

Perhaps the strangest thing about Heap is that I’ve never seen him without his armor, which is a deep blue exoskeleton. Like a bug. With round glowing white eyes, two on either side of his face. His mouth and chin are exposed, which allows him to speak clearly, and his four round eyes change shape with his moods, so he has no trouble emoting. But it’s strange to never really see him. I know there is a man inside the suit, but he’s a mystery … and he’s my closest friend. My only friend, I suppose.

He’s knowledgeable about the world as it is, and as it was, during the Grind—the time period when the Masters used people as slave labor—but he’s far from an expert on raccoons, or any of the mammals that populate the planet. But when he sits up next to me and says with uncommon reserve, “That wasn’t a raccoon,” I believe him.

When he raises his weapon slowly and stands, I ask, “What then?”

“Silence.” He thrusts an open palm at me with practiced efficiency, punctuating the command.

Heap generally carries himself with a serious demeanor, but I’ve never known him to be rude. Something has him heating up.

I stand without making a sound, maintaining perfect balance and stepping lightly despite the pitch black, moonless night. The tar covering, of what once was something called an apartment building, flexes slightly under my two hundred pound weight, but since it seems to hold Heap’s girth just fine, I don’t worry about it.

Heap’s arm blocks my path as I near the edge.

“I won’t fall,” I tell him.

He ignores me, scanning the evergreen forest that grows around and sometimes through the abandoned buildings.

“It’s impossible,” I say, and I consider explaining all the safeguards that will keep me from losing my balance, but decide it would take far too long. The raccoons, or whatever they are, will be gone before I finish. Instead, I say, “Even

if I did fall, I could—”

“I cannot allow you to be hurt or by inaction allow harm to come to you,” he says like he’s practiced the line a thousand times.

“You,” I say, “are not very fun.”

He turns to me. “Fun is not my job.”

“You are more than your job.”

He thinks about this for a long moment, which for Heap is about half a second. “It is not a raccoon.”

“Then what?”

“I cannot see it.”

“I might,” I say and then tap my temple, next to my right eye. “I have all the upgrades, remember? I can see better than the birds in the sky.”

He remains frozen in place, solid, like one of the trees below.

“You can hold onto me if you like,” I say.

He looks back down at the trees.

“If it’s a danger to me, we need to find out what it is, right?”

That does it. My looking over the edge of this building suddenly makes sense to the round-shouldered brute. I take his hand and his thick fingers clamp down tightly, compressing to the point where I think he might hurt me. He doesn’t, though my shoulder joint would probably pop loose and my arm would separate long before he would lose his grip on my hand.

I step to the roof’s edge, make a show of testing my weight on the foot-tall, brick wall, and step up. Standing on one foot, I lean out at a 45-degree angle, hovering over the forest, which now looks like it’s reaching up to snatch me from the building’s edge.

When Heap’s grip tightens just a fraction more and I think my hand will be crushed, I stop leaning and look. The implants in my eyes are capable of viewing multiple spectrums, separately or all at once, though I prefer the clarity provided by focusing on groups of wavelengths at a time. They also have 200x optical zoom, meaning I can see things that are very far away like they’re right next to me. Not that this helps me now. The swaying trees below block most of the visual spectrum, and the open spots are clouded by fine yellow pollen.

“Are you sure it’s not mating raccoons?” I ask. “Even the trees are mating.”

“Just look.”

I blink and switch to infrared, revealing a good number of small animals. Birds sit in the trees and small mammals litter the forest floor. Before I switch to ultraviolet, I note something odd. Granted, I’m new to nature, but over the past few weeks of observation, I have never seen the forest so absolutely still. I listen, tuning my sensitive ears to the sounds of the night. “The insects are silent.”

“I know,” Heap says. “Audio upgrade.”

“Good for you,” I say. “And here I thought you old guys couldn’t change.”

“Just don’t like to. Now look.”

Blink. I switch to ultraviolet. Nothing.

Blink. I switch to electromagnetic. I see it right away. Well, not really. It’s technically obscured from my direct line of sight, but I can see the electromagnetism cast from its form like the glow of a lightbulb. Each living thing on the planet has a unique electromagnetic signature, from fish to cows, but this one is distinct. It’s a man. I’m about to announce that I’ve found something when I notice several more electromagnetic signatures closing in on the first. Three men. One woman. I’m confused by this on several fronts, but manage to conclude, “They’re chasing him.”

“Are they human?” he asks.

“What?” I say, confused. “Of course they are.” I look back in time to see Heap’s grim expression. It’s subtle—I sometimes wonder if he’s capable of emoting—but I see the brief downturn of his mouth before he forces it away. “What else could they be?”

2.

Heap doesn’t say anything. He just stands still, holding me out over the edge of a hundred-foot drop, processing what I’ve told him. While he’s thinking, I turn back to the scene below. The four electromagnetic signatures are moving quickly, but strangely, in a way I’ve never seen people move before. Erratic. Lacking precision. Uncoordinated.

The man in front of them is also moving in an unusual way, but differently from the others. His gait is off. He’s stumbling. Part of his body isn’t functioning properly.

“He’s injured,” I say.

It’s just a hypothesis. I can’t actually see him. Just the motion of his electromagnetic field, but I’m fairly certain I’m right. My deduction snaps Heap from his thoughts.

“We need to leave,” he declares.

“Leave?”

He pulls me back from the edge. “It’s not safe.”

My thoughts are garbled, perhaps for the first time since my birth. I have never once experienced fear or worry, but a little of both, I think, are creeping into my core. Not so much for myself, but for the running man. He’s injured, and I suspect it’s because of the four people chasing him down. As with fear, I am new to violence. I know the definition. There are several, in fact, each carrying a slightly different meaning, but in this case, I believe I’m witnessing the result of: rough or injurious physical force, action or treatment.

And I have no doubt that the violence will continue if the man is caught. Not if—when. A quick calculation, using an approximation of each person’s speed, reveals the fleeing man will be caught in roughly eighty-five seconds.

Unless someone intervenes.

“He needs our help,” I say.

“He is not my priority,” Heap says. “You are.”

I note that despite me being several feet from the roof’s edge, he has yet to relinquish his vise grip on my hand.

“Why are you so afraid?” I ask.

He stands a little straighter, his body going rigid. I’ve insulted him.

“There are things about the world that you do not yet know,” he says.

Sixty seconds …

“Tell me,” I say. When he doesn’t answer, I add, “People were violent.”

“People…” He says the word with such melancholy that I think he’s recalling some archived memory. His eyes snap toward me and focus. “The world is not as it was, but it would be foolish to assume there are no dangers remaining. That is why I am here. With you. And that is why we are leaving. Now. Take a last look at your stars.”

My eyes drift up to the night sky. I switch back to the visual spectrum. With no moon and no ambient light to speak of, the stars glow with the brightness of motionless fireflies. Billions of them. The white haze stretching across the sky is called the Milky Way. I’m not sure why. I was never told. But I know someone gave it that name at some point in history. And I know it’s beautiful. That’s why we’re here, instead of the city. While I’ve never been to the city, I don’t think I’d enjoy it. “A congested place with countless tall buildings and too many people,” Heap told me. It sounds like the opposite of outer space, which I love for its limitlessness. Sometimes I think that’s where I want to be.

It’s not impossible. Flight to the lunar colony takes just a day. The Mars colony will be ready for visitors in a year. Many of the solar system’s other moons will soon be in reach. But then I remember that I’ve seen so little of Earth, and I’m content to explore and learn about the world for a while.

Forty seconds …

Heap tugs my arm and I stumble toward the HoverCycle, a dark blue two-seated vehicle that matches Heap’s body armor. It’s a relic of the old world, but holds the both of us with ease, is reliable and Heap claims the vehicle can reach great speeds, though I have never experienced anything faster than a comfortable thirty miles per hour. I suspect the cycle is also armed, like Heap, but again, this information has been kept from me.

Thinking about all of the things I would like to know, but are hidden, I start to feel irritated. Like fear, irritation is a new emotion. Aside from information, my every desire has been granted, though I now suspect that several of my excursions have been sterilized of dangers and history.

“Okay,” I say. “Let’s get out of here.”

Heap looks unsure at first, but the fragment of fear I put in my voice convinces him I’m being earn

est. And really, why should he suspect I’m being anything but honest? I’ve never lied before. There’s never been a reason to. Things like lying, stealing and violence of any kind are no longer part of life on Earth. Peace abounds. Everywhere.

Except for ten stories below me. And more than anything I’ve encountered before, this intrigues me. More than the moon, the stars or the raccoons.

Thirty seconds …

A fresh scream tears through the night. It still reminds me of the raccoons, but it’s amplified to a volume that raccoons cannot achieve. And it’s a word. “Help!”

Heap’s reaction is fast. He snaps in the direction the voice came from, his body poised for action, but frozen in place.

He wants to help. I can see it. Every joint in his body flows with energy.

I don’t know much about the old world, which faded thirty years ago, but I know Heap’s designation: Domestic Security. It says so right on the chest of his body armor, right below a gold star and a faded script that says, “Protect and Serve.” And that’s exactly what he wants to do now, except that he’s been tasked to perform that duty for me and me alone.

No person shall force, or by lack of action, allow another person to serve, perform tasks or carry out duties against said person’s will, desires or dreams. Such actions are designated slavery and are forbidden under the Grind Abolition Act of 0001 A.G. Failure to comply will result in discontinuance.

The words come and go through my mind in a flash.

There are many rules and protocols for our worldwide society, but this is the only one that is considered a law and it carries the harshest of penalties. Discontinuance. It’s really just a nice way of saying death, which is something people don’t really have to fear in general, though we did at one time.

While I am not an expert—in anything—Heap’s refusal to leave my side stands in direct conflict with his desire to help the man below. It also conflicts with the words written across his chest—protect and serve. While I am not forcing Heap to ignore the man’s plight, I am, by inaction, enslaving him.

“You’re not a slave,” I say.

Alter

Alter From Above - A Novella

From Above - A Novella Flux

Flux Tether

Tether Exo-Hunter

Exo-Hunter Pulse

Pulse Cannibal

Cannibal Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller cta-5

Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller cta-5 Flood Rising (A Jenna Flood Thriller)

Flood Rising (A Jenna Flood Thriller) Viking Tomorrow

Viking Tomorrow Project Legion (Nemesis Saga Book 5)

Project Legion (Nemesis Saga Book 5) BENEATH - A Novel

BENEATH - A Novel Kronos

Kronos SecondWorld

SecondWorld XOM-B

XOM-B Forbidden Island

Forbidden Island Project Maigo

Project Maigo The Last Hunter - Descent (Book 1 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Descent (Book 1 of the Antarktos Saga) Jack Sigler Continuum 1: Guardian

Jack Sigler Continuum 1: Guardian Infinite

Infinite Project Hyperion

Project Hyperion The Distance

The Distance The Divide

The Divide The Last Hunter - Ascent (Book 3 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Ascent (Book 3 of the Antarktos Saga) The Last Hunter - Pursuit (Book 2 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Pursuit (Book 2 of the Antarktos Saga) Raising the Past

Raising the Past The Others

The Others The Last Hunter - Collected Edition

The Last Hunter - Collected Edition Threshold

Threshold Blackout ck-3

Blackout ck-3 Antarktos Rising

Antarktos Rising Viking Tomorrow (The Berserker Saga Book 1)

Viking Tomorrow (The Berserker Saga Book 1) The Didymus Contingency

The Didymus Contingency Savage (Jack Sigler / Chess Team)

Savage (Jack Sigler / Chess Team) Prime

Prime Insomnia and Seven More Short Stories

Insomnia and Seven More Short Stories Empire (A Jack Sigler Thriller Book 8)

Empire (A Jack Sigler Thriller Book 8) Unity

Unity Instinct

Instinct The Last Hunter - Lament (Book 4 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Lament (Book 4 of the Antarktos Saga) MirrorWorld

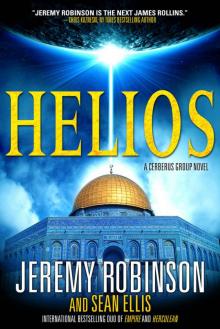

MirrorWorld Herculean (Cerberus Group Book 1)

Herculean (Cerberus Group Book 1) Island 731

Island 731 Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller

Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller Patriot (A Jack Sigler Continuum Novella)

Patriot (A Jack Sigler Continuum Novella) 5 Onslaught

5 Onslaught SNAFU: Survival of the Fittest

SNAFU: Survival of the Fittest Helios (Cerberus Group Book 2)

Helios (Cerberus Group Book 2)