- Home

- Jeremy Robinson

Flux Page 11

Flux Read online

Page 11

“Wha’d you do to my arm?” Buck shouts, clutching the limp arm.

The pain and tingling consuming his limb will fade in seconds. I scramble to my feet, mentally preparing a series of strikes I think will end the fight. But the moment I stand, the world starts to spin, and I drop back to my knees.

Buck grins at my delirium and takes a step toward me, cocking back his still fully functional left fist.

Then he flinches to a stop. His eyes roll back as he snaps rigid and then falls facedown into the snow.

My father stands behind him, clutching the shotgun he used to club Buck. “No offense,” he says, “but you were getting your ass kicked.”

I laugh. I’ve never heard my father say anything remotely unsavory, but like many parents, the guarded language used around children fades when they’re out of earshot.

He reaches down a hand and yanks me to my feet. While he binds Buck’s hands behind him, I trudge over to Boone, who’s just coming to. Before he can push himself up, I put a knee into his back and let my weight rest on it. “I’m going to ask you some questions, and if I don’t like your answers…”

Motion draws my attention uphill.

Young Owen is out of hiding and watching me closely.

Behind him, the mountain is lost in a cascade of shimmering light.

18

“Owen!” my father shouts, his arms outstretched toward his son.

I’m faster than I remember being, sprinting down the mountainside, eyes wide. “It’s happening again!”

The sound of his voice is drowned out by the growing buzz and rumble.

“It will pass,” I say, attempting to reassure my father. “We’ll be okay.”

He says nothing, but gives me a serious stare after collecting Owen in his arms. As a father, his sole mission right now is to keep my younger self safe. The look in his eyes says he has no idea how to do that, and that he doesn’t share my faux confidence, though he attempts to hide that from Owen.

“Just close your eyes and hold on,” he says. “It will pass. Just let it pass. Stay relaxed, just like before.”

I find myself taking his advice. While keeping my weight on Boone’s back, I let myself relax, welcoming the flux, rather than resisting it.

Boone, on the other hand, loses his shit. He hasn’t lived through this yet. Hasn’t been torn from his own time and deposited in another. Hasn’t seen the distorted wave rolling down the mountain, or experienced the thunderous roar of its passing. His scream blends in with the cacophony of sound.

I close my eyes to avoid feeling sickened by the sight of the world shattering and bending around me. My insides twist as the effect passes through us, but it’s not nearly as bad this time. When the sound of it races downhill, I open my eyes again.

Steam rises from my wet arms. Goosebumps rise up as the temperature shift hits my skin. It’s at least eighty degrees. For a moment, I think it’s summer again, but then I look up and find the trees covered in buds, ready to sprout leaves. A warm spring, the air perfumed with the smell of new growth. This is my favorite season in Appalachia. It feels hopeful, even if nothing has changed for most of the people living in these mountains.

Beneath me, Boone heaves. I stand before he can puke, watching as he retches into the damp, leafy forest floor. “What…” he manages to say, but that’s all he gets out. He doesn’t need to finish the question.

“I’ll wait ’till you’re done giving your lunch back to the Earth,” I say, “then I’ll attempt to explain what I know—” I meet my father’s eyes, and then my own. “—to all of you.”

It takes Boone’s body another thirty seconds to stop revolting against the sudden shift through time. He pushes himself against a tree trunk, staring up at the blue sky above, now easily visible through the collection of ruby buds. “Where is the snow?”

All the fight and bravado have fled Boone. He’s now just a confused and weary man. His friend, Buck, has been spared the negative effects of being carried through time on account of his being unconscious. He’ll be thrown for a loop when he wakes up, both from the shift in time, and the concussion he’ll no doubt be sporting.

Speaking of concussions… While some of my nausea fades, a good portion remains. I’m not a hundred percent steady on my feet, either. All thanks to Buck’s giant fists. If I don’t get some rest soon, reaching Synergy and finding Cassie and Levi will be the least of my problems.

I collect my father’s rifle from the ground, where it’s partially embedded in soil. Has the terrain changed? It looks largely the same, but it’s possible the ground has shifted. I glance uphill and note that fallen tree behind which my father and Owen hid is now standing tall.

My eyes widen as I consider the horrifying question: what happens if time shifts and you’re standing where a tree once was? Or even worse, another person?

“Ain’t you gonna answer me!” Boone looks close to losing his mind. A man of his education during this time period is more likely to chalk up the change in season to witchcraft. Appalachian people have always been a superstitious lot, believing in supernatural hoodoo as surely as they do Jesus Christ.

I sit down across from him, rifle cradled in my lap. I massage my temples and try to think of a way to explain what’s happening.

“Hey,” my father says. He’s standing above me holding out a hand. “For your pain.”

I hold my hand out and accept three acetaminophen pills. Then he unclips a water bottle from his hip and offers it. I take the pills and the water, grateful for my father’s preparedness. I nod my thanks, swallow the pills, and turn to Boone. “I’m going to ask you a question, and I want a straight answer.”

When he says nothing, I ask, “What year is it?”

His face screws up. “Now why would—”

“Answer the question,” I growl, my patience for long-dead assholes at an end.

“1887,” he says. “Now what—”

I hold out a hand, silencing him. I look my father in the eyes. “And what about you two? What’s the year?”

“1985,” Owen answers.

“That ain’t…” Boone shakes his head. “You’ve lost your minds.”

“And for you?” my father asks, already catching on.

“2019.”

I see a flicker of surprise in my father’s eyes, then resignation to the fact that we’re being tossed through time.

Owen, on the other hand, is thrilled. “You’re from the future?”

“Horseshit,” Boone mumbles.

“Are there flying cars?” Owen asks. “A colony on Mars? Teleporters?”

I forgot how much I used to love science fiction. “None of those things. But we do have the Internet.”

He’s hardly impressed.

“And robots that look like people.”

His eyes widen. “Like the Terminator?”

“Arnold Schwarzenegger was the governor of California,” I say, remembering that I had a poster of him in full Conan regalia, posing with Red Sonja, on my bedroom wall.

“Whoa,” my young self says, now impressed with the future, despite the lack of flying cars and interplanetary colonies.

“Fail to see how he’d make a worthwhile governor,” my father says. “More muscle than brains.”

“You don’t even want to know who our president is.” I chuckle, picturing my father’s response to the news. He’s a staunch Republican, but in the 80s politics still had a measure of sanity. Then again, it was Reagan who ushered in the age of celebrities becoming politicians.

“I’m sorry,” Boone says, and then shouts, “But I don’t know what in tarnation you all are going on about! Where is the damned snow? Where the hell are we?”

“We haven’t gone anywhere,” I tell him. “We’re still on the same mountainside. Still in the same woods. We’re just in a different time period.”

“What’a you mean, ‘time period?’”

“I mean it’s no longer 1887.”

“And what year are you

proposing it is?”

I shrug. “No way to know unless we meet someone. Since the first wave in 2019, I’ve experienced four jumps back in time. The first was 1985.” I look at my father. “That’s when I ran into you in the truck. We were still trying to figure it out.”

“But you knew something was off,” my father observes. “I saw the way you were avoiding looking at me. Even now, it’s making you uncomfortable.”

I see where the conversation is going, and I know where it ends, but I’m not sure I’m ready for that, and I have no idea what the consequences might be. When it comes to Boone, and Chafin, and Arthur, and all the men associated with them, I can’t think of a solid connection to my future. But my father and my younger self… Everything said and done in their presence could affect my future.

“Best guess,” I say, hoping to shift the conversation away from that questionable subject, “we’re sometime in the 1800s. Longest jump back so far was sixty four years.”

“But you don’t know. They could be longer.”

I shake my head. “I don’t know much of anything, aside from the fact that the people responsible for all this are at the top of this mountain.”

“At the mine?” my father asks.

“Ain’t nothing up there but stone and wind,” Boone says.

“In my time, the mine is closed.” I note the disappointed look on my father’s face. He invested his life—literally—in that mine, and he believed in its long-term potential to transform our community. “A company named Synergy bought Adel and a lot of the land in and around town. I’m not really certain about what they were doing, but I know there was a lot of cutting edge science involved.”

“You’re saying we’ve been caught up in some kind of physics experiment gone wrong?” my father asks.

“That’s pretty much the gist, yeah.”

“And you know this because…”

“I work for them.”

My father tenses.

“In security,” I add. “I didn’t know what they were doing, and I honestly still don’t. But I aim to find out, and if I can, set things right.”

“Then we’ll be joining you,” my father says.

“I ain’t going nowhere with any of you all,” Boone says. “Might as well shoot me now. Get it over with.”

I push myself to my feet, doing my best to hide my continuing state of wooziness. I brandish the rifle, letting it make up for my lack of physical prowess. “You’re going to go back to your people and see that they’re okay. Then you’re going to not attack, kill, or capture anyone you might come across, from any time. If you find someone, tell ’em what you know and try to keep them with you. Whatever enemies you had, they’ve likely not yet been born. You understand?”

“Can’t say I understand.” Boone pushes himself up. “But I’ll do what you ask until I find out you’re lying or this is some kind’a hex.”

I motion to Buck, who’s just beginning to stir. “And take him with you.” The rifle is heavy in my hands, but I manage to raise it toward Boone’s head. “Now then, before all that, what about my friends? Are they alive?”

Boone nods. “Last I saw ’em.”

“And that was?”

“Downhill. About a quarter mile. Farther, by now, if they haven’t been caught.”

“How many men did you send after them?”

“Ten.”

“Anything I can say to make them believe you sent me to stop them?”

“Shoot enough of ’em and they’ll start listening,” he says with a lop-sided grin. When I don’t smile with him, he clears his throat. “Apologies. That wasn’t actually a joke. Just struck me funny, is all.”

I sigh at the idea of taking more lives, but I’m not fond of my only other option. When Buck grunts and rolls himself over, stunned and disoriented by the change in scenery, I motion to him and say, “Explain the situation as best you can to your man, here. Send him back to your people.”

“What about me?” Boone asks.

“You’re coming with us.” I look to my father, and without saying a word ask if he’s alright with that arrangement. I probably should have asked him first, but I’m not about to abandon Cassie and Levi, and there’s no way I’m letting my father and Owen out of my sight.

A subtle nod from my father confirms our plan moving forward and that all the admiration and affection I’ve had for my father’s memory wasn’t tainted by the many years without him. He’s as brave and strong-willed as I remember…only I don’t remember this. If I did, at least I’d have some inkling of what we might run into on this time-fractured mountainside. Based upon my experiences so far, I’m pretty sure it will be nothing good.

19

The next thirty minutes is a rather boring hike leading downhill, away from my ultimate goal, but toward the people I’ve sworn to protect, a promise that now extends to my father and young Owen. At least, I think we’re headed toward Cassie and Levi. Tracking them is all but impossible thanks to the missing snow and the new set of trees. Any tracks they had left—footprints, bent branches, gouges in bark—have been erased by time, in reverse.

All that remains of Cassie’s and Levi’s flight are mostly concealed bullet casings, and the occasional dead body. Each time we come across a corpse, I’m terrified it will be one of them, but one after another, we uncover Boone’s men. He reacts with a kind of detached disappointment, muttering about each man’s failings.

But then we run out of bullets and bodies to follow.

And honestly, I’m relieved. Cassie and Levi left a long trail of corpses in their wake. I don’t blame them for it. Boone’s men would have done the same to them. But this morning, Cassie set out for another boring day on the job, and Levi to break into my house to steal drugs for his grandmother. Neither of them would have guessed they’d be forced to gun down a variety of men, though I suppose that’s normal compared to being shunted back in time.

I’m reluctant to shout for them. I don’t know who or what is hunting these woods, but experience has taught me to err on the side of caution. So I’ll have to track them with logic.

I’ve counted six bodies. That means four of Boone’s men are still alive. It’s been a while since I saw a 9mm casing, so it’s likely Cassie and Levi are just on the run now. To put the most distance between themselves and the men chasing them, they’d follow the path of least resistance. In this case, that’s downhill.

I glance toward Adel’s peak, cloaked in forest, impossible to see from here. I’m separated from my ultimate goal by a long hike. Moving farther from Synergy isn’t going to solve our long-term problems, but I’m bound by loyalty.

For now.

There will come a time when I put the mission first. ‘No man left behind’ is a nice sentiment, but it’s always coupled with the unsaid ‘but not at the risk of mission failure.’ That’s the cruel nature of combat. If Cassie and Levi were soldiers, I’d have already abandoned the search and struck out for Synergy. I’m sure Minuteman is following that course of action, which is why I need to seriously start thinking about doing the same.

He struck me as a decent man, but also very well trained, and seeming decent is easy for a disciplined sociopath. I have no idea what his plan is, or how many people are on his team, but I can’t imagine him breaching the facility without confronting my people.

Fifteen more minutes, I tell myself, then we’re turning back.

“Worried about your friends?” my father asks, Owen’s hand clasped in his. My child self has been chomping at the bit, wanting to run ahead despite the danger. I remember running up and down Adel while my father trudged behind, not because he was out of shape, but because he carried all our gear. I think it made him happy, to see me enjoying the forest that meant so much to him, but now…he’s got a vice grip on Owen’s hand.

“They’re tough and smart,” I say, the words sounding hollow. When he raises a skeptical eyebrow, I smile. “How can you tell?”

“You purse your lips,” he sa

ys. “Like someone else I know.” He glances down at Owen, who’s oblivious to the conversation, as his eyes dart from tree to tree, squeezing his lips together.

“Huh…”

“So what’s it like, in the future?” he asks.

He’s trying to take my mind off my worry, parenting without knowing that’s actually his role in my life. “In some ways, it’s the same. You’d recognize most of it. Everything is a little shinier and sleeker, but not completely unrecognizable.”

“So no USS Enterprise?”

“There’s an international space station,” I say, which catches Owen’s attention. “Some people have lived in space for more than a year.”

“They can do that?”

“Well, they stretch out a bit, and they lose a lot of muscle mass on account of the zero gravity, but light speed travel is still a ways off. I suppose a space station is kind of Star Trek. Oh…” I dig into my pocket and feel the slender shape of my phone, which Boone’s men failed to take. “And we do have these.”

I hand the device to my father, but it fully captivates both Owen and Boone, who has slowed his pace to take part in the conversation. “That thing made of obsidian?”

“Hardly,” I say, and I push the power button. When the screen glows to life Boone reacts as though he’s been struck by lightning. “Tarnation!”

“Whoa,” Owen says, reaching out for the device.

When I look down at the screen, I have a moment of panic. My lock screen wallpaper is a photo of my grandfather and me, taken two years after my father had passed. I hold my thumb over the sensor, quickly unlocking the phone and switching the screen to a collection of app icons over an image of the Appalachian mountains at sunset.

“What is it?” Owen asks, as I let him take it from my hand.

“It’s like a tricorder and a tablet computer in one,” I say, knowing he and my father will both understand the references. Boone is out of luck, but I really don’t give a shit. “Technically it’s a telephone, but it can do a lot more. They’re called smartphones.”

“Like the Apple IIc?” Owen asks.

Alter

Alter From Above - A Novella

From Above - A Novella Flux

Flux Tether

Tether Exo-Hunter

Exo-Hunter Pulse

Pulse Cannibal

Cannibal Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller cta-5

Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller cta-5 Flood Rising (A Jenna Flood Thriller)

Flood Rising (A Jenna Flood Thriller) Viking Tomorrow

Viking Tomorrow Project Legion (Nemesis Saga Book 5)

Project Legion (Nemesis Saga Book 5) BENEATH - A Novel

BENEATH - A Novel Kronos

Kronos SecondWorld

SecondWorld XOM-B

XOM-B Forbidden Island

Forbidden Island Project Maigo

Project Maigo The Last Hunter - Descent (Book 1 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Descent (Book 1 of the Antarktos Saga) Jack Sigler Continuum 1: Guardian

Jack Sigler Continuum 1: Guardian Infinite

Infinite Project Hyperion

Project Hyperion The Distance

The Distance The Divide

The Divide The Last Hunter - Ascent (Book 3 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Ascent (Book 3 of the Antarktos Saga) The Last Hunter - Pursuit (Book 2 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Pursuit (Book 2 of the Antarktos Saga) Raising the Past

Raising the Past The Others

The Others The Last Hunter - Collected Edition

The Last Hunter - Collected Edition Threshold

Threshold Blackout ck-3

Blackout ck-3 Antarktos Rising

Antarktos Rising Viking Tomorrow (The Berserker Saga Book 1)

Viking Tomorrow (The Berserker Saga Book 1) The Didymus Contingency

The Didymus Contingency Savage (Jack Sigler / Chess Team)

Savage (Jack Sigler / Chess Team) Prime

Prime Insomnia and Seven More Short Stories

Insomnia and Seven More Short Stories Empire (A Jack Sigler Thriller Book 8)

Empire (A Jack Sigler Thriller Book 8) Unity

Unity Instinct

Instinct The Last Hunter - Lament (Book 4 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Lament (Book 4 of the Antarktos Saga) MirrorWorld

MirrorWorld Herculean (Cerberus Group Book 1)

Herculean (Cerberus Group Book 1) Island 731

Island 731 Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller

Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller Patriot (A Jack Sigler Continuum Novella)

Patriot (A Jack Sigler Continuum Novella) 5 Onslaught

5 Onslaught SNAFU: Survival of the Fittest

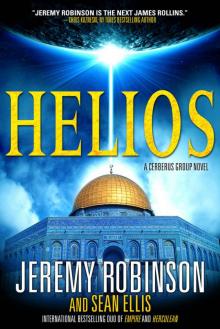

SNAFU: Survival of the Fittest Helios (Cerberus Group Book 2)

Helios (Cerberus Group Book 2)