- Home

- Jeremy Robinson

The Divide Page 12

The Divide Read online

Page 12

“Maybe so,” he says, “But have you ever seen an animal, predator or prey, eating peppermint?”

I have not, but don’t say so.

“What you won’t smell like, is food,” he adds.

I release his wrist and allow him to finish. He’s gentle, the way Grace would be, careful to not rub the oil into my wounds. Then he steps back. “How do you feel?”

My eyes blink water from the peppermint fumes, but the strength dissipates as the oil is absorbed. I’m about to complain about the discomfort, and the burning, when I notice the pain in my head has dulled. I roll my neck back and forth. “Better.”

I take two steps, ready to continue our trek at a faster pace. I pause long enough to say, “Thank you,” and then run, as much toward my son as away from my gratitude. I’m not sure why I thanked him. He brought me and my son to a hellish place and might very well have doomed all of New Inglan. But his simple kindness and careful ministrations could not be overlooked. Plistim is not the violent rebel we were all told about. He is more like my father than I would like to admit.

The journey south continues at an acceptable pace. The forest is unending, carved by the occasional river and grassy clearing. I look for signs of ancient cities, but I manage only to spot a few vine-laden walls, which might have once been something, or nothing. I don’t stop to inspect.

After two hours, I slow to a walk. “We’ve gone far enough.” While I have no real way to know how far Salem’s balloon traveled before descending, my gut says we’re close. But the land here is so vast, we could search these woods for weeks without spotting any sign of Salem, or his balloon.

That’s why they’ll use fire and smoke, I realize. It’s dangerous, but necessary. How else could they find each other in an unfamiliar land?

“When will they light a fire?” I ask.

Shua stops beside me, eyes on what little of the sky can be seen through the trees. “Should have already. Also, in case something happens and we’re separated, we won’t find them at the fire. They’ll leave a trail, at least a mile long, for us to follow.”

“That…makes sense,” I admit. “But how are we supposed to spot smoke from here?” I motion at the trees concealing the sky.

“We didn’t even know if there would be trees,” Plistim said. “This is a new world. We planned as best we could.”

“I can climb,” Shoba says, looking up at the trees.

I shake my head. “The branches will be too thin to support your weight long before you’re high enough to pierce the canopy.”

“But—”

“I’ve climbed more trees than any one of you, probably than all of you combined. I’ve spent the last two years of my life eating, sleeping, living, and shitting in trees. We’re not going to waste time so you can prove to me what I already know.”

Shoba looks at Plistim with a ‘do I really have to listen to her’ expression, and to my surprise, he responds, “Davina is right. We would be better served by finding a hill, or a clearing.”

“Then we should head that way,” Shoba says, pointing east.

I’d been so intent on following a southward course that I hadn’t spent much time looking east or west. Once I do, I know the girl is right. Yellow sunlight glows through the trees, revealing a spot of land where nothing grows. It could be rocky terrain, a natural clearing, or even the remains of a concrete foundation, preventing any new growth for hundreds of years.

I strike out toward the clearing, resuming my quick pace and then speeding up as we draw nearer. At first, my run is fueled by anticipation. At spotting smoke. At finding Salem. And then, it’s fear that drives me. The nearer I get to the clearing, the more I’m positive it’s not natural or some consequence of ancient construction.

Fallen trees litter the forest floor, some toppled with their roots upturned, others shattered. The smell of pine and sap is thick in the air.

Entering the clearing, I leap from tree to tree until I’m standing in the center. The clearing is only twenty feet across, but it stretches out of sight in either direction.

This isn’t a clearing.

It’s a path.

I note a large footprint, where green leaves have been crushed into the muddy soil.

“You said the Golyat headed north.” Once again, my anger is barely contained. I don’t look back at the others. I’m speaking to all of them.

“It must have circled back,” Shua says.

“Why would it do that?” Shoba asks.

I lock eyes with Shua. He knows as well as I do that a predator wouldn’t change course so drastically, and with such destructive fervor, without a reason. We saw the Golyat from the balloon, moving through the forest without destroying everything in its path. It didn’t decimate the landscape until it detected me.

“It’s hunting them,” Plistim says, despair creeping into his voice.

“Or,” I guess, “It saw their fire.”

“There have been natural fires over the course of the past five hundred years that didn’t signify prey,” Plistim says. “Why would it—”

“Because we taught it differently,” I say.

I move back to the forest, where the sky is blotted out, but the ground is clear of fallen trees. Then, in direct disobedience to the Prime Law and everything I’ve been taught, and believe, I follow the Golyat’s path.

The trail of destruction leads us through miles of terrain, some of it rough, some of it level. We traverse it all, never slowing and in complete silence. I would run like this day and night until we find Salem…or what’s left of him.

It’s not until I hear the distant chatter of the hungry Golyat that I slow. The thumping was distant, and muffled by the forest, but it still sets me on edge. We’re getting close. My stomach churns, in part from the sound’s effect, but also from the knowledge that I might not like what we find.

Favoring stealth over speed now, I creep onward, spending a half hour covering the next mile in silence. The others follow my lead, stepping where I step, and never speaking. Modernists are good sheep, which I imagine is why they agreed to follow Plistim across the Divide en masse.

The cleared path widens ahead, revealing a broad circle of destruction similar to what we saw upon leaving our den this morning.

This is where they came down, I think, looking for the balloon, but spotting nothing more than fallen trees. I stop short of the clearing, hidden behind a tree. I let my other senses see what my eyes can’t.

The forest is lush with leafy decay and pollen. There is a trace of wood smoke, but not enough to signify a fire. But it could be the remnants of the flames that had held another balloon aloft.

Then I smell something else. Another kind of decay, but mixed with something pungent and acidic. Like bile. And blood. And shit. And piss. As a hunter, these are all scents I’m accustomed to, but not when they’re distinctly human. I’m not sure if the Golyat remains nearby, but I know for certain that people died in the clearing ahead.

I make it one step before Shua catches my arm and mouths the word, “Wait.”

With a hard yank, I’m free and running. I enter the clearing, unsure of what to expect, and totally unprepared for what I find. If not for the severed arm at my feet, I’m not sure I could have identified the swirl of humanity scattered on the ground, and across the trees, reaching thirty feet up.

I fall to my knees, tears in my eyes, and retch into the blood-stained ground, adding my fresh bile to the mix of foul odors.

20

I’m not alone on my knees. Plistim falls with a groan of anguish. The dead are his family, too. Despite all the horrible things I’ve been taught about the Modernist leader, he’s still just a man. A father. A grandfather. As his body shakes, bare hands gripping the blood-soaked ground, I have little doubt that he loves his family, which includes my son.

Shua moves through the carnage with a hand to his mouth and tears in his eyes, but he hasn’t come undone. Shoba stands still and quiet, her brown skin pale. Her face triggers my maternal

instincts.

I push up from the ground and keep my eyes on the girl. She glances my way, and when we make eye contact, she nearly cracks. Tears flow down her cheeks. A tremble starts in her fingertips and runs up her arms.

“I—I—I…” Shoba’s lips quiver.

When I reach for her, she sobs and falls into my arms. I barely know the girl, but I give her all the comfort I can muster, holding her close, stroking her back, kissing her head.

“I’ve got you,” I tell her. “I’ve got you.”

“I—I’ve never seen anything like this.” Shoba’s voice is muffled by my chest, which is good because the high pitch would be audible from a distance. But I don’t have the strength to shush her.

“No one has,” I tell her.

“I have,” Shua says, making eye contact with me. It’s the first time I’ve seen anything like displeasure from him, directed toward me. I’m about to ask him what he’s talking about when he adds, “The Cull was meant to be a message. To the Modernists. But the savagery of it…”

“It gave us resolve,” Plistim says. “It was the moment we knew the people of New Inglan would never accept us, or our ideas. To stay was to suffer, and to live under the constant threat of a violence that we now know mirrors the Golyat’s brutality.”

I have nothing to say.

What can I say?

I have always believed the Cull to be a horrible thing, but also a necessary thing. Hell, I was nearly a willing participant in a recreation of the event. While I was unaware that the Cull was so…revolting in its execution, dead is dead. What Shoba, Plistim, Shua, and I are feeling now—the despair, revulsion, and desperation? This is what they would have suffered back then, but at the hands of their fellow man, not a monster.

While Shoba weeps into my chest, I watch Shua work his way through the scene. What’s he doing? When he crouches down, picks up an arm severed at the elbow, and inspects it, I cringe. Then he places the limb down, delicately, like he could damage it further. He extends two fingers on his left hand.

He moves through the carnage, inspecting bits and pieces, extending two more fingers.

He’s identifying the dead, I realize, and counting them.

Shoba stops weeping, wipes her eyes, and steps back like she’s just switched off the part of her that feels. “Did you find them all?”

Shua stops his search, hands on his hips, looking desperate to leave. He shakes his head. “Not everyone.”

“Who’s missing?” Plistim asks.

“Del, Holland, and his wife,” he says, but then he looks in my eyes, unashamed of the tears wetting his cheeks. “And Salem.”

Emotion overwhelms me, a mix of desperate hope and fear. “Don’t say that if you’re not sure. Don’t you dare say that.”

“They’re not among the dead,” Shua says. “Whether or not they still live…”

That there is a chance Salem is still alive is enough to pull me from the emotional brink. I work my way through the dead, taking note of the various body parts still recognizable as human. While I can’t identify those that I see, I’m sure none of them is Salem.

I pause at the clearing’s core, where Shua crouches atop a blood-free, fallen tree trunk.

I wince when I see what he’s looking at, not because I know what it is, but because of how it smells.

“I’d appreciate it if you didn’t react,” he whispers.

“To the smell?” I say, now trying hard to keep my nose from crinkling.

“When you figure out what it is.”

The ominous words make me forget all about the odor, and the death surrounding us.

I stare at the dark gray, semi-liquid mass that appears to be spreading into various states of viscosity. The middle is somewhat solid, swirling up to a flaccid cone. Toward the outside edge, the mass is soupy, and lumpy. The outer edge is a clear liquid that’s oozing into the forest floor, and…I lean a little closer…dissolving it.

What the hell?

It’s my nose that ultimately solves the riddle. The scent wafting up is something like shit. Charred shit. The smell of digested meat is masked, but unmistakable. It’s Golyat shit.

As I begin to process that, hiding my shock and revulsion becomes nearly impossible. This isn’t just Golyat waste, it’s what’s left of their family members, who were not only killed and strewn about, but eaten and hastily passed back to the earth.

“I think we should go,” I say, trying to sound calm. I stand and survey the area, as though trying to determine which way to proceed, but I’m really just trying not to look back down.

Shua stands with me. “We just need to find their trail. They are not adept at covering their tracks.”

“Or surviving in the wild,” Shoba adds, with the voice of a girl on the fringe of giving up.

I leave what can be best described as a circle of death and decay, happy to return to the forest, which feels alive and fresh in comparison, where just a tinge of hope still remains. When the others join me, I say, “Salem is smart. He wouldn’t just hope that we’d find their trail, he’d leave one for us.”

Plistim nods, already scanning the area.

“If they left on foot, and not in the Golyat’s hands,” Shoba says.

“Enough of that,” Plistim snaps.

“Let’s split up,” I say, and I point to Shua and Plistim. “You two head around that way.” I motion to the left. “I’ll take Shoba around the other way. If they left a trail, we’ll find it.”

Shua looks to Plistim, unsure. I’m sensing my normal assertiveness might be as unappreciated here as it was in New Inglan. Plistim has been the Modernist leader since their inception. They’re probably not accustomed to someone else—not to mention an outsider who had planned to kill them—taking the lead. So I justify the decision with, “Shoba lacks experience, and Plistim—no offense—has aging eyes.”

Plistim is nodding before I finish. “A sound plan.” He turns and starts walking away, waving for Shua to follow him.

I start in the other direction without a word. Shoba isn’t exactly a light foot. I know she’s following without looking back.

With each step I sweep the area, looking for any sign of passage. It doesn’t take long to spot a broken branch. I bend to inspect it.

“Is that…” Shoba looks at the branch, the break fresh and partial.

“It was them,” I say, “but not on their way out.” I bend the branch, revealing the break that could have only happened by someone entering the clearing.

“You’re sure?”

I hate to crush the flicker of hope in her voice, but there’s no doubt. I point to the footprint a few feet away, toes pointed toward the clearing. “There’s no heel print. They were running.”

I stand and move on, stopping when I reach signs of a very different path. The signs are almost too big to notice, and Shoba misses it. “What do you see?”

“Up there,” I say, pointing to the trunk of a tall pine. Thirty feet up, the bark has been sheared off. Then I point to the ground around us. The foliage is compact, and the saplings dotting the forest floor stand at an angle, still trying to right themselves after being crushed. “We’re standing in a footprint.”

To our right are more signs of the Golyat’s passage, slower and more careful after satiating itself on Shoba’s family. “The Golyat went this way, which means…”

“Salem and the rest went the other way,” Shoba finishes, and she’s right.

I look across the clearing. Shua and Plistim are moving at a slower pace, having a heated and hushed conversation. They haven’t found anything yet, but I suspect they’ll be the ones to spot Salem’s path.

When I start moving again, I walk a bit faster and spend less time searching for signs of passage. We’re too close to the Golyat’s trail. Shoba stays close and quiet, never questioning our new pace.

“Who is Del?” I ask. “Another one of Plistim’s many descendants?”

“She is family,” Shoba says, “but like you

, not a blood relative.”

“Oh?”

“She’s…a wife.”

I’m gripped with fresh sadness. Had Del seen her husband and children slain and consumed by the Golyat? “Married to one of Plistim’s sons?”

“No,” Shoba says, offering me a sympathetic smile. “To yours.”

“To my what?”

“To your son,” she says. I’m still confused, but her next words make everything clear. “Del is Salem’s wife.”

The news locks me in place. “My son…is married. But he’s just a boy. A child.”

“Less of a child than when you knew him,” Shoba says, and before I can complain anew, she adds, “Don’t be harsh on Plistim for marrying them. Salem loves her. Adores her. But crossing the Divide…it was just for family. For her to come, they had to be wed.”

“When did this happen?” I ask, feeling more sorrow at having missed this part of my son’s life, than anger at Plistim for allowing the union.

“A week ago.”

A bird call flutters across the clearing. It’s convincing, but also unlike any bird in the forest. Shua waves at us from across the clearing. In my haste, I nearly decide to cross through the gore, but I decide against it, not as a mercy to myself, but to Shoba.

We hurry around the clearing, no longer looking for signs of passage. As we close in on Shua and Plistim, I see it before Shua points it out. A symbol is carved into the bark of a maple tree, the wound still fresh. I place my hand on the carved symbol and whisper, “Salem.”

“You recognize this symbol?” Plistim asks.

“I don’t know what it means,” I tell him, “but I know Salem carved it for me.”

“For you?” Shua sounds slightly offended.

But then I put the matter to rest by drawing my blade and showing him the edge. Near the handle of what my father said was once called a KA-BAR knife, a symbol has been etched, and it’s unmistakable.

While I have no idea what the symbol once stood for—and apparently neither does Plistim—I know what it means now: Salem is alive, and he’s left a trail for me to follow.

Alter

Alter From Above - A Novella

From Above - A Novella Flux

Flux Tether

Tether Exo-Hunter

Exo-Hunter Pulse

Pulse Cannibal

Cannibal Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller cta-5

Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller cta-5 Flood Rising (A Jenna Flood Thriller)

Flood Rising (A Jenna Flood Thriller) Viking Tomorrow

Viking Tomorrow Project Legion (Nemesis Saga Book 5)

Project Legion (Nemesis Saga Book 5) BENEATH - A Novel

BENEATH - A Novel Kronos

Kronos SecondWorld

SecondWorld XOM-B

XOM-B Forbidden Island

Forbidden Island Project Maigo

Project Maigo The Last Hunter - Descent (Book 1 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Descent (Book 1 of the Antarktos Saga) Jack Sigler Continuum 1: Guardian

Jack Sigler Continuum 1: Guardian Infinite

Infinite Project Hyperion

Project Hyperion The Distance

The Distance The Divide

The Divide The Last Hunter - Ascent (Book 3 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Ascent (Book 3 of the Antarktos Saga) The Last Hunter - Pursuit (Book 2 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Pursuit (Book 2 of the Antarktos Saga) Raising the Past

Raising the Past The Others

The Others The Last Hunter - Collected Edition

The Last Hunter - Collected Edition Threshold

Threshold Blackout ck-3

Blackout ck-3 Antarktos Rising

Antarktos Rising Viking Tomorrow (The Berserker Saga Book 1)

Viking Tomorrow (The Berserker Saga Book 1) The Didymus Contingency

The Didymus Contingency Savage (Jack Sigler / Chess Team)

Savage (Jack Sigler / Chess Team) Prime

Prime Insomnia and Seven More Short Stories

Insomnia and Seven More Short Stories Empire (A Jack Sigler Thriller Book 8)

Empire (A Jack Sigler Thriller Book 8) Unity

Unity Instinct

Instinct The Last Hunter - Lament (Book 4 of the Antarktos Saga)

The Last Hunter - Lament (Book 4 of the Antarktos Saga) MirrorWorld

MirrorWorld Herculean (Cerberus Group Book 1)

Herculean (Cerberus Group Book 1) Island 731

Island 731 Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller

Omega: A Jack Sigler Thriller Patriot (A Jack Sigler Continuum Novella)

Patriot (A Jack Sigler Continuum Novella) 5 Onslaught

5 Onslaught SNAFU: Survival of the Fittest

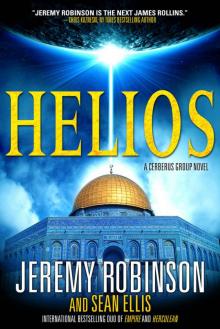

SNAFU: Survival of the Fittest Helios (Cerberus Group Book 2)

Helios (Cerberus Group Book 2)